I Turned on a Dating Sim to See Pretty Girls and My Game Console Got Hacked

Helloyunho @helloyunho@hackers.pub

You turned on your PlayStation to see the pretty girls trapped in a game. Just then, your friend says, "I've cleared this route, want to check it out?" and gives you their save file. Since you missed the opportunity to take that route yourself, you decide to use your friend's save to see it. After registering the save and loading the dating sim... suddenly your console freezes and ends up formatting its internal storage!

... Of course, the above isn't a real story, but it could certainly happen. With what I'm about to explain in this article.

yarpe

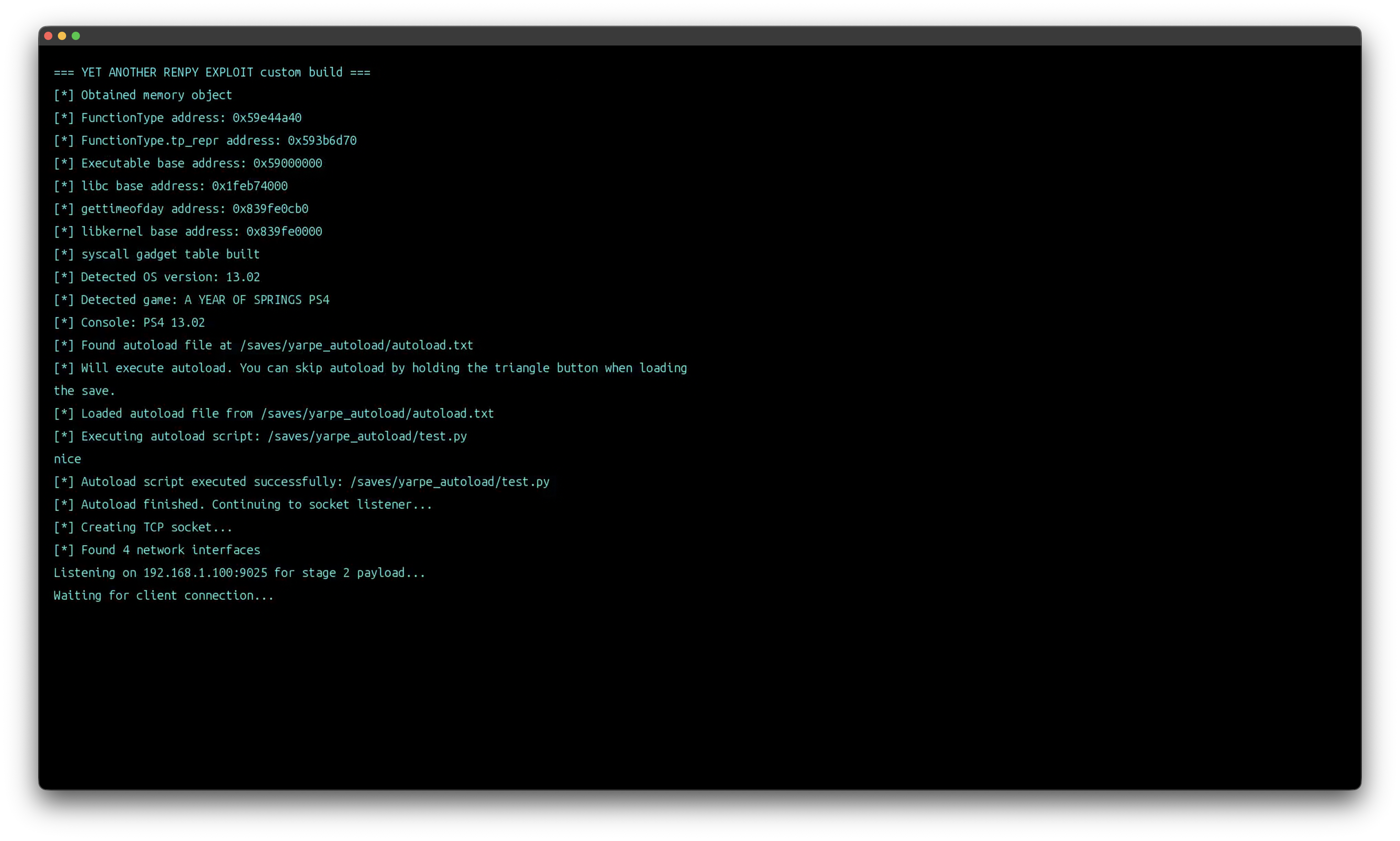

Introducing yarpe (Yet Another Ren'Py PlayStation Exploit)!

This script exploits vulnerabilities in Ren'Py-based PlayStation games, and currently works with the following games:

- A YEAR OF SPRINGS PS4 (CUSA30428, CUSA30429, CUSA30430, CUSA30431)

- Arcade Spirits: The New Challengers PS4 (CUSA32096, CUSA32097)

But how did all this begin, and how was it created?

Xbox One/Series

Actually, I wasn't interested in PlayStation (I'll abbreviate it as PS from now on). Instead, I was very interested in Xbox. When the first kernel vulnerability for Xbox One/Series appeared, I noticed a game save vulnerability in Warhammer: Vermintide 2 that allowed game dumping. That's when I thought: "Could other games have similar save vulnerabilities?" A friend who shares my interest in this kind of work first recommended games made with RPG Maker (often called "Tsukuru"). Unfortunately, RPG Maker games on consoles used different save structures, making ACE (Arbitrary Code Execution) impossible.

Then it suddenly occurred to me: "Don't Ren'Py games use Pickle for saves?"

Pickle

Python has a serialization method called Pickle. It has the characteristic of being able to serialize (almost) any Python object.

But what if there's an object that can't be serialized as a property of a class, and you want to serialize that class? Python supports a method called __reduce__ for this purpose. This specifies what data should be used to reconstruct the class when it's serialized/deserialized.

It's used like this:

class A:

def __init__(self, a):

self.a = a

self.b = "b"

def __reduce__(self):

return self.__class__, (self.a,)

# serialize

a = A()

b = pickle.dumps(a)But what if __reduce__ contains another Python function? For example, something like exec?

class Exploit:

def __reduce__(self):

return exec, ("print('Hello, World!')",)

exploit = Exploit()

a = pickle.dumps(exploit)

pickle.loads(a) # Hello, World!...Yes, when Pickle loads, it executes the code contained in the string... This is why the official Python Pickle documentation states that Pickle is not secure.

Playing with Ren'Py Games Using Just One Save

Now that we know Ren'Py uses Pickle and that we can execute code with Pickle, it's time to try it ourselves!

Ren'Py saves have filenames like 1-1-LT1.save. While it looks fancy, it's just a Zip file with the extension changed to .save.

If you extract it with a common Zip program, several files appear, but the one we're interested in is the log file. This file contains Ren'Py's Pickle data.

Now if we replace this file with a Pickle containing our own code, compress it again and insert it...?

The code executes! That's brilliant!

Code Execution Works, Now What?

Now that we know code execution is possible, what's the next step? Memory manipulation, of course! After a quick search on Google, I came across a repository called unsafe-python. This repository enables direct memory access in Python.

The vulnerability exploits the fact that the LOAD_CONST opcode doesn't perform any range checking, allowing us to create fake PyObjects. Using this, we can create a bytearray object that spans from address 0 to essentially the end of 64-bit address space, giving us direct memory access.

Now we can modify any memory location as long as we know its address! As a bonus, Python's lovely slicing syntax makes this even more convenient.

# Assume we got raw memory bytearray

mem = getmem()

mem[0x18000000:0x18000008] = b'\0' * 8Now that we can manipulate memory freely and create PyObjects, all we need to do is store our own program in memory, create a Python function object that points to our code, and we're done!

...if only it were that simple...

Memory Region Permissions

Memory regions have specific permissions assigned to them. Read, Write, and eXecute permissions are separated, and as the name suggests, without execute permission, you cannot run that memory region as code.

The problem is that the areas we typically write to only have read and write permissions, but no execute permission! If we try to execute a region without execute permission, the CPU will generate a permission error, leading to a segfault.

So how can we execute our desired commands with these limited memory permissions? The answer lies in ROP.

ROP

ROP, or Return Oriented Programming, literally refers to code that operates based on the ret assembly instruction.

The characteristic of the ret instruction is that it takes the address value written at the current CPU stack pointer (the RSP register in x86_64) and writes it to the instruction pointer (the RIP register in x86_64), then moves the stack pointer. What if, when executing ret, we make the stack pointer point to our desired code (which is in an executable memory region)?

To do this, we need to find memory addresses that end with ret and execute our desired commands. We call these "gadgets".

You might wonder if permission errors could occur with the stack pointer as well, but the memory region pointed to by the stack pointer only needs read and write permissions, so it's fine.

With this knowledge, we can formulate a plan:

- Create a custom stack using a Python list.

- Place appropriate gadgets in the custom stack.

- Create a Python function object that points to a gadget that changes the stack pointer to our desired address (in this case, the address of the Python list's elements).

- Execute this Python function object. The stack pointer moves,

retis called, and our desired commands are executed!

...Many details are omitted, but this is roughly the plan. Now it's time to create the exploit using this approach!

Finding Gadgets

As mentioned earlier, finding appropriate gadgets is crucial for ROP. I used the ROPgadget tool for this. When you run the tool with your desired executable, it finds all assembly instructions that end with ret, along with their memory addresses! (Even considering virtual memory addresses!)

There are two approaches from here:

- Dynamically find gadget addresses by reading executable memory

- Create a pre-defined

dictwith the addresses of these gadgets

While method 1 could be used on Xbox One/Series, for PS I had to use method 2 due to reasons I'll mention later.

Moving the Stack Pointer to Our Desired Address

Now we need to move the stack pointer to our Python list address, but how? What we want is (for x86_64) mov rsp, ??? followed by ret. The ??? part is crucial because we need to understand how Python function calls work and the function calling convention of the CPU and OS being executed.

The function calling convention refers to which register each argument goes into when calling a function.

The x86_64 function calling convention order for Linux/UNIX-based OS is: RDI, RSI, RDX, RCX, R8, R9

And Python function calls work like this:

function_call(PyObject* func, PyObject *arg, PyObject *kw)

Therefore, if we found an instruction like mov rsp, [rdi + 0x30]; ret, we would need to place our desired stack address at around offset 0x30 in our custom Python function object. If we found mov rsp, [rsi + 0x10]; ret, we would need to create a custom tuple object, store the stack address at around offset 0x10, and call our function object like my_func(*custom_tuple).

Everything's Ready to Execute... But It Crashes Without Returning to Python?

I forgot the most important part of ROP. After executing our custom stack, we need to return to the original stack.

In my case, I used the instruction push rbp; mov rbp, rsp; xor esi, esi; call [rdi + 0x130] to save rsp in rbp before executing my desired commands (at rdi + 0x130 is the instruction that changes the stack pointer).

After executing the desired commands, I used mov rsp, rbp; pop rbp; ret to return to the original stack pointer.

Is this enough? No. Doing just this causes an error when Python tries to reference the function's return value (the RAX register in x86_64) and gets an incorrect value. So what should we do?

The answer is to return the None object. This gives Python a valid value to return, preventing errors. (And yes, None is also an object.)

One thing to note is that we need to increase the refcount of the None object by 1. Otherwise, when Python tries to decrease the refcount of the return value, an underflow problem could occur.

Once this is done, we can finally execute our desired commands!

Testing on Xbox!

With help from the Xbox One Research team, I received Ren'Py game files, found gadgets, and ran the test!

Testing on Xbox first, I successfully opened a socket and executed another Python script through that socket! (Note that the game doesn't support Python's socket module by default.)

In the case of Xbox, I could use functions very similar to Windows, which made the process more straightforward.

The Anticipated PS...

A few months after testing on Xbox, I became interested in PS hacking as well.

The differences I discovered between Xbox and PS were:

- Uses a FreeBSD-based OS

- Has its own syscalls

- Executables loaded in memory don't have ELF headers (can't determine Import table)

- Can only load modules recorded in the executable

- For PS5: Cannot read memory regions containing executables (XOM)

...The reason I used method 2 in Finding Gadgets is because of XOM (eXecutable Only Memory). Actually, method 1 could be used on PS4, but I wanted to support PS5 games as well.

With help from the PS5 Research & Development Discord server, I received game files, found gadgets, and wrote the code in the same way.

Despite the constraints listed above, the basic operation was similar, so I could create it without major issues, and the test result...!

It worked successfully, and yarpe was born.

Conclusion

Getting to this point took almost a year (with breaks in between). While creating this, I found it more fun than difficult. (Though I seem to have reduced my sleeping hours while working on it.)

Before concluding, I'd like to acknowledge the people who helped me along the way.

- Xbox One Research team: They provided the starting point for this project and were tremendously helpful in constructing the core components. (tuxuser, LukeFZ, Billy, harold, and others provided assistance.)

- Dr.Yenyen: Provided PS4/5 game files and conducted numerous tests.

- Gezine: Answered my questions and pointed out errors while developing the vulnerability.

- Sajjad: Conducted many tests alongside Dr.Yenyen.

- cow: Directly compared files and fixed problematic areas.

- earthonion: Conducted tests and provided much advice.

Thank you for reading this lengthy article.