I've tended to assume that much of ML is simply about more data and bigger neural nets but I've really enjoyed studying up on "Conditional Flow Matching" which I think is genuinely beautiful mathematics. Not Group Theory or Riemann Surface beautiful, but beautiful nonetheless.

The problem it solves is this: given a pair of probability distributions p0 and p1, find a function f with the property that if x is drawn from p0 then the marginal distribution of f(x) is p1. p0 and p1 are both in a form that we can sample from, but we can't necessarily write an expression for the density [1].

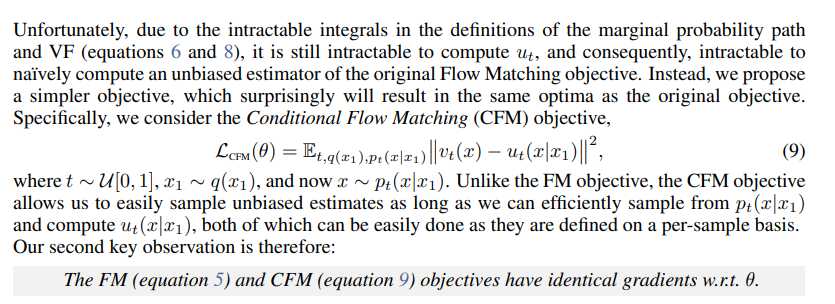

The first astonishing thing is how easy it is to write down a minimisation problem whose solution is f. When I say easy, it's not at all obvious a priori that this is the thing you need, but once you see it, it's incredibly easy to implement in software. Once you have the minimisation objective, you keep drawing pairs (x0,x1) independently from p0 and p1 and update f using standard gradient descent.

But the really surprising thing is that the optimisation is secretly solving another more important problem. When I say "secretly" I mean I went through the process of proving the process I mentioned above is correct, implemented code from more or less from scratch (using Jax), tested it, saw that it worked, but still failed to appreciate that it had also solved another problem from the world of optimal transport. But that's already too much for mathstodon...

https://arxiv.org/abs/2210.02747

[1] I've complained about this before: *computationally* a probability density you can compute, and a distribution you can sample from, are entirely different, but conventional notation conflates them. Makes papers hard to read sometimes.