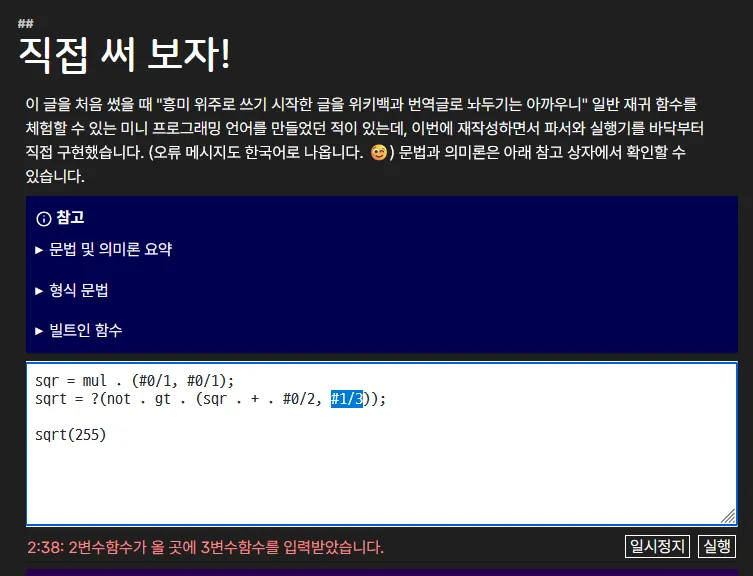

네이버는 클로바 나눔손글씨를 이런 식으로 배포하는 걸 멈춰주길 바란다... 폴더가 없으면 그냥 전체선택해서 우클릭 설치가 되는데 굳~~~이 폴더를 나눠놓아서 mv $(ls ./**/*.ttf) ..를 하게 만들기나 하고 어?

잇창명 EatChangmyeong💕🐱

@eatch@hackers.pub · 21 following · 26 followers

*Encounter the Wider World*

🏠

- eatch.dev

🦋

- @eatch.dev

🐘

- @EatChangmyeong@planet.moe

🐙

- @EatChangmyeong

📝₂

- blog.eatch.dev

📝₁

- eatchangmyeong.github.io

어제는 새로 산 노트북에서 블로그 작업을 시작하려고 하니까 unocss 때문에 pnpm dev가 아예 안 돌더라.... 안그래도 마이그레이션하려고 생각하고 있었는데 잘됐다 하고 tailwind로 바꾸기로 했다

안좋은 점: 이거를 하느라 7시까지 밤을 샜고 아직 안끝났다 💀

어제는 새로 산 노트북에서 블로그 작업을 시작하려고 하니까 unocss 때문에 pnpm dev가 아예 안 돌더라.... 안그래도 마이그레이션하려고 생각하고 있었는데 잘됐다 하고 tailwind로 바꾸기로 했다

In cultures like Korea and Japan, taking off your shoes at home is a long-standing tradition. I'm curious about how this practice varies across different regions and households in the fediverse.

How does your household handle shoes indoors?

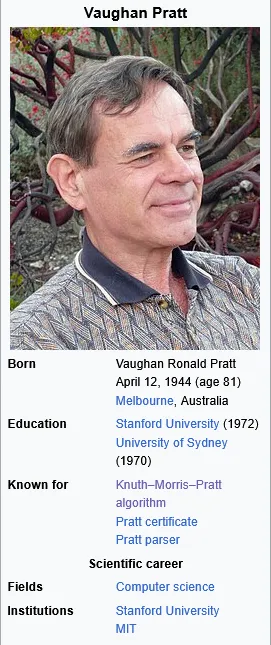

어 뭐야 KMP의 P랑 Pratt parser의 Pratt이 동일인물이라고???

어째서 다들 노동자가 아니라 사용자에게 이입하는 걸까…?

오늘 본 유튜브 동영상에서 '네가 AI보다 잘난 게 뭐냐. 네 코드가 AI보다 낫다는 걸 증명하지 못하면 취업은 꿈도 꾸지 마라' ← 이런 정서가 너무 짙게 느껴져서 힘들었다...

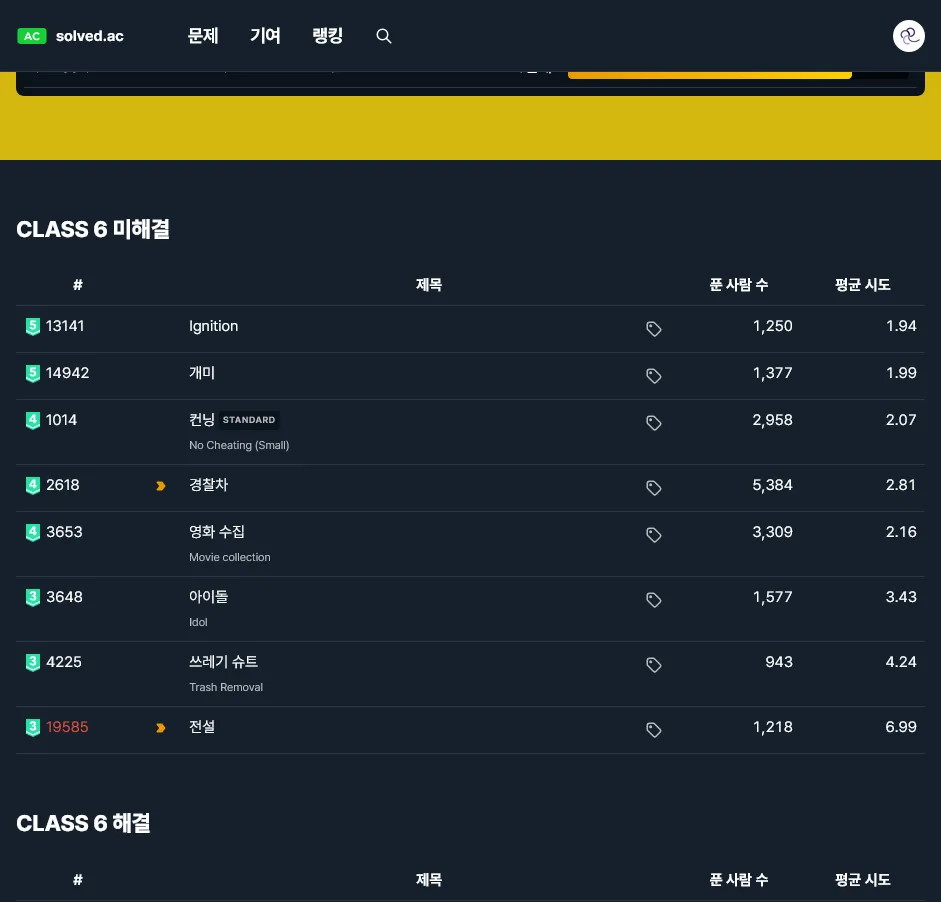

6+단까지 2문제 남았는데 한 문제는 아직 깊게 생각을 안해봤고 한 문제는 죽어라 시도해도 계속 TLE가 난단 말이지...

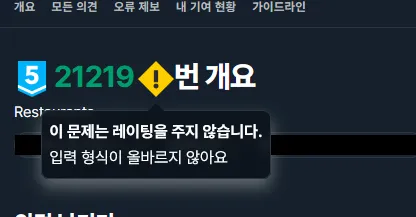

오랜만에 Claude로 들어가니까 이런 오류가 난다...... 쓰지 말라는 신의 계시인가

이 상태로 억지?로 프롬프트를 넣어봤는데 뭔가 시스템 프롬프트가 적용이 안된 것마냥 말투가 좀 다르고 좋은 질문입니다, 또 물어보실 것이 있으신가요 이런 말을 안한다

오랜만에 Claude로 들어가니까 이런 오류가 난다...... 쓰지 말라는 신의 계시인가

[투표] 나는 2^63-1 = 9223372036854775807을 외울 수 1️⃣ 있다 2️⃣ 없다 📊 Show results

[투표] 나는 2^32 = 4294967296을 외울 수 1️⃣ 있다 2️⃣ 없다 📊 Show results

Been thinking a lot about ![]() @algernonsmall rodent who dislikes browsers very much's recent post on FLOSS and LLM training. The frustration with AI companies is spot on, but I wonder if there's a different strategic path. Instead of withdrawal, what if this is our GPL moment for AI—a chance to evolve copyleft to cover training? Tried to work through the idea here: Histomat of F/OSS: We should reclaim LLMs, not reject them.

@algernonsmall rodent who dislikes browsers very much's recent post on FLOSS and LLM training. The frustration with AI companies is spot on, but I wonder if there's a different strategic path. Instead of withdrawal, what if this is our GPL moment for AI—a chance to evolve copyleft to cover training? Tried to work through the idea here: Histomat of F/OSS: We should reclaim LLMs, not reject them.

AI 企業이 F/OSS 코드로 LLM 訓練하는 걸 막을 게 아니라, 訓練한 모델을 公開하도록 要求해야 한다고 생각합니다.

撤收가 아니라 再專有! GPL이 그랬던 것처럼요.

訓練 카피레프트에 對한 글을 썼습니다: 〈F/OSS 史唯: 우리는 LLM을 拒否할 게 아니라 되찾아 와야 한다〉(한글).

빨리 저런 라이센스가 제대로 잘 만들어져서 내 레포에 적용하고 싶다.

근데 그런 라이센스가 있다한들 AI 기업들이 그걸 존중할까 하는 걱정이 있는데. 한가지 긍정적인건 LLM들이 원본 데이터를 하도 잘 외워서(이게 꼭 긍정적이지만은 않다), 가령 유명한 소설 '위대한 개츠비'를 한번 읊어보라 하면 80% 정확도로 뱉더라 라던 연구가 있다. 그래서 라이센스를 어기고 학습에 사용한 코드가 있다면 검출은 쉬울지도?

모델 프로바이더 입장에서는 시스템 프롬프트에 '코드를 외웠다는 사실이 드러나지 않게하라' 같은걸 넣을수도 있겠다. 근데 또 모델이 나쁜짓을 하게 하면 딱 그지시만 따르는게 아니라 전반적으로 부작용이 생긴다는 연구가 있다(해당 연구에선 프롬프팅이 아니고 파인튜닝이었지만). 그래서 라이센스를 어기고 학습한다음 잡아떼기가 생각보다 어려운 일일수 있겠다.

잇창명 EatChangmyeong💕🐱 shared the below article:

생성 AI 논의에 대해 두서없이 몇 가지

lark @lark@hackers.pub

오랫동안 머신러닝 딥러닝 AI 모델링을 업으로 삼아 왔지만 정작 LLM이나 이미지 생성 같은 생성쪽은 피해다니다 보니[1] 이쪽 주제에 대해 아는 척 하기도 쉽지 않지만.. 관련 논의들 구경하다 보면 제가 평소 생각하는 중요 지점들이 잘 이야기되지 않는 것 같아 의식의 흐름을 따라 이것저것 남겨봅니다.

우선 모델이 생성한 결과물이 어떤 성격이나 맥락을 가지는지에 따라 저작권 문제가 완전히 달라지는데, 이건 원래 저작권에 대한 전반적인 성격이 그러하기 때문입니다. 기존 저작물을 복사/변형하더라도 그 목적이 원래 저작물과 판이하게 다를수록 저작권 침해가 아니라 fair use로 인정받을 가능성이 높아집니다.

맥락과 의도가 얼마나 중요한지를 보여주는 상징적인 사례가 구글 북스 소송인데, 구글 북스는 저작권이 있는 책을 사용자들에게 그대로 보여주니까 심각한 저작권 침해로 보일 수 있지만, 법정에서는 구글 북스 웹사이트가 원래 책 내용을 그대로 접근하는 목적을 막고 검색이라는 새로운 목적에만 사용가능하도록 했다고 판단했습니다.

이러한 다양한 사례 연구들이 Foundation Models and Fair Use에 나와 있습니다. 이 논문은 AI 연구자들과 법학 연구자가 같이 썼고 여러 legal edge case가 등장해서 생각을 정리하는 데에 도움이 될 수 있습니다.

Fair use의 핵심 요소인 transformative에 대해 AI모델 입장에서 보면, 사용자가 준 입력 텍스트에 있는 정보를 추출하거나 변환하는 task가 이에 해당할 가능성이 높습니다. 가장 유명한 예시가 텍스트 번역일 것 같은데, 사용자가 입력한 텍스트를 다른 언어로 바꾸는 것이 전부고 거기에 새로운 창작성이 드러나지는 않습니다[2]. 제가 이해하기로는 LLM이나 소위 AI가 잘 한다고 알려진 task도 대부분 이러한 것입니다. 번역이라든지, 텍스트 포맷을 바꾼다든지 등등. 제 주변에 LLM 잘 활용하신다는 분들을 보면 아마도 대부분 그렇게 쓰시는 것 같고요.

여기서 UX 관점에서의 불평을 하고 싶은데요, 무조건적인 텍스트 생성이 아니라 주어진 입력을 변환하는 능력이 LLM의 핵심 가치라면 모델이나 서비스 입장에서 그런 기능만 제공하고 지나친 생성을 제한하는 UI나 기술 장치를 도입해야 하지 않을까요? LLM을 긍정적으로 생각하지만 전반적인 생성(특히 입력보다 출력이 더 자유도가 높을 경우)이 사회적으로 위험하다고 생각된다면 그러한 조치를 LLM 서비스 제공자들에게 요구할 수는 없을까요? 저는 이러한 방향의 논의를 거의 본 적이 없는데, 아마 LLM를 접해본 사람들은 긍정적이든 부정적이든 그런 인터페이스가 어쩔 수 없는 일이라고 가정하고 있어서 그런 것 같습니다. (마침 며칠 전부터 ChatGPT나 Gemini에 번역 전용 UI가 생겼다는 소식이 보이고 있습니다. 이 글을 조금 더 빨리 쓸 걸 그랬네요..)

프로그래밍 쪽에서도 비슷하게 코드를 생성하는 사용법보다는 코드를 읽고 정보를 추출해주는 쪽이 저작권이나 윤리 문제가 적고 프로그래머의 능력 향상에 도움이 되지 않을거라고 생각하고요. (제가 상상하는 최적의 코딩 AI agent는 Rubber duck에 가까운데, 모든 질문과 해답이 제 머릿속에서 나와야 한다고 생각합니다. 그 중 문제 해결이나 능력 향상에 명백히 도움 안 될 질문만 잘 쳐내주면 좋겠어요.)

cf: 최근 Moral Codes를 조금씩 읽고 있습니다. 프로그래밍과 UI와 LLM과 윤리에 대한 책입니다. 아직 전부를 차근차근 읽은 건 아니지만, 기존의 LLM 논의가 갖혀있던 프레임에 빠져나오는 데에 큰 도움이 될 수 있다고 보여서 이 주제에 관심이 있는 분들에게 추천합니다. Open access라 무료로 볼 수 있어요.

Generative AI in Servo에서 제시하는 potential exceptions가 제 분야와 정확하게 겹칩니다. ↩︎

현실적으로는 학습 데이터 오류 등으로 입력에 없던 내용이 튀어나오는 문제가 있습니다. Hallucination이라는 용어가 LLM 논의할때 주로 나오지만 실제로는 번역 task 연구 논문에서 처음 제시된 용어이고 해당 분야에서 이 문제는 오랫동안 중요하게 인지되어 왔습니다. ↩︎

뒤에서 2번째라는 의미의 penultimate라는 단어가 있다는 걸 기억하고 뒤에서 3번째라는 단어도 있나 찾아봤는데 대충 접두사 하나씩 더 붙이고 '나는 뒤에서 3번째야' '나는 뒤에서 4번째야' '나는 뒤에서 5번째야'라고 주장하는 단어들이 있어서 웃기다

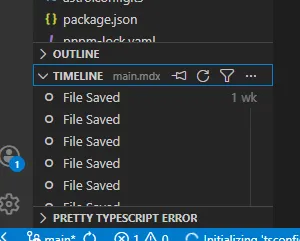

공익글: VS Code에서 작업하던 파일이 유실됐다면 가장 먼저 Timeline부터 확인합시다. 바로 오늘도 이 방법으로 삭제된 코드를 복구한 지인분이 계시며...

debugging be like:

루비문제풀었다!!!!!!!!! 축하해주세요

ㅇㄴ 내 레이팅 돌려줘!!!!!!

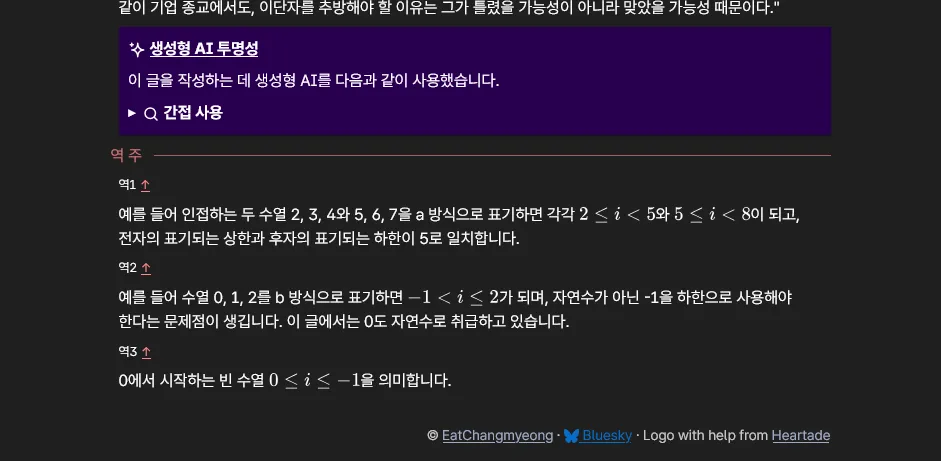

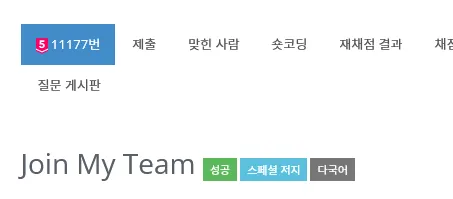

LLM에서 마크다운이 널리 쓰이게 되면서 안 보고 싶어도 볼 수 밖에 없게 된 흔한 꼬라지로 그림에서 보는 것처럼 마크다운 강조 표시(**)가 그대로 노출되어 버리는 광경이 있다. 이 문제는 CommonMark의 고질적인 문제로, 한 10년 전쯤에 보고한 적도 있는데 지금까지 어떤 해결책도 제시되지 않은 채로 방치되어 있다.

문제의 상세는 이러하다. CommonMark는 마크다운을 표준화하는 과정에서 파싱의 복잡도를 제한하기 위해 연속된 구분자(delimiter run)라는 개념을 넣었는데, 연속된 구분자는 어느 방향에 있느냐에 따라서 왼편(left-flanking)과 오른편(right-flanking)이라는 속성을 가질 수 있다(왼편이자 오른편일 수도 있고, 둘 다 아닐 수도 있다). 이 규칙에 따르면 **는 왼편의 연속된 구분자로부터 시작해서 오른편의 연속된 구분자로 끝나야만 한다. 여기서 중요한 건 왼편인지 오른편인지를 판단하는 데 외부 맥락이 전혀 안 들어가고 주변의 몇 글자만 보고 바로 결정된다는 것인데, 이를테면 왼편의 연속된 구분자는 **<보통 글자> 꼴이거나 <공백>**<기호> 또는 <기호>**<기호> 꼴이어야 한다. ("보통 글자"란 공백이나 기호가 아닌 글자를 가리킨다.) 첫번째 꼴은 아무래도 **마크다운**은 같이 낱말 안에 끼어 들어가 있는 연속된 구분자를 허용하기 위한 것이고, 두번째/세번째 꼴은 이 **"마크다운"** 형식은 같이 기호 앞에 붙어 있는 연속된 구분자를 제한적으로 허용하기 위한 것이라 해석할 수 있겠다. 오른편도 방향만 다르고 똑같은 규칙을 가지는데, 이 규칙으로 **마크다운(Markdown)**은을 해석해 보면 뒷쪽 **의 앞에는 기호가 들어 있으므로 뒤에는 공백이나 기호가 나와야 하지만 보통 글자가 나왔으므로 오른편이 아니라고 해석되어 강조의 끝으로 처리되지 않는 것이다.

CommonMark 명세에서도 설명되어 있지만, 이 규칙의 원 의도는 **이런 **식으로** 중첩되어** 강조된 문법을 허용하기 위한 것이다. 강조를 한답시고 **이런 ** 식으로 공백을 강조 문법 안쪽에 끼워 넣는 일이 일반적으로는 없으므로, 이런 상황에서 공백에 인접한 강조 문법은 항상 특정 방향에만 올 수 있다고 선언하는 것으로 모호함을 해소하는 것이다. 허나 CJK 환경에서는 공백이 아예 없거나 공백이 있어도 한국어처럼 낱말 안에서 기호를 쓰는 경우가 드물지 않기 때문에, 이런 식으로 어느 연속된 구분자가 왼편인지 오른편인지 추론하는 데 한계가 있다는 것이다. 단순히 <보통 문자>**<기호>도 왼편으로 해석하는 식으로 해서 **마크다운(Markdown)**은 같은 걸 허용한다 하더라도, このような**[状況](...)**は 이런 상황은 어쩔 것인가? 내가 느끼기에는 중첩되어 강조된 문법의 효용은 제한적인 반면 이로 인해 생기는 CJK 환경에서의 불편함은 명확하다. 그리고 LLM은 CommonMark의 설계 의도 따위는 고려하지 않고 실제 사람들이 사용할 법한 식으로 마크다운을 쓰기 때문에, 사람들이 막연하게 가지고만 있던 이런 불편함이 그대로 표면화되어 버린 것이고 말이다.

근데 솔직히 마크다운이 "너 진짜 **핵심**을 찔렀어"의 형태로 대중화가 될 줄은 몰랐지...

잇창명 EatChangmyeong💕🐱 shared the below article:

Designing type-safe sync/async mode support in TypeScript

洪 民憙 (Hong Minhee) @hongminhee@hackers.pub

I recently added sync/async mode support to Optique, a type-safe CLI parser

for TypeScript. It turned out to be one of the trickier features I've

implemented—the object() combinator alone needed to compute a combined mode

from all its child parsers, and TypeScript's inference kept hitting edge cases.

What is Optique?

Optique is a type-safe, combinatorial CLI parser for TypeScript, inspired by Haskell's optparse-applicative. Instead of decorators or builder patterns, you compose small parsers into larger ones using combinators, and TypeScript infers the result types.

Here's a quick taste:

import { object } from "@optique/core/constructs";

import { argument, option } from "@optique/core/primitives";

import { string, integer } from "@optique/core/valueparser";

import { run } from "@optique/run";

const cli = object({

name: argument(string()),

count: option("-n", "--count", integer()),

});

// TypeScript infers: { name: string; count: number | undefined }

const result = run(cli); // sync by defaultThe type inference works through arbitrarily deep compositions—in most cases, you don't need explicit type annotations.

How it started

Lucas Garron (@lgarron) opened an issue requesting

async support for shell completions. He wanted to provide

Tab-completion suggestions by running shell commands like

git for-each-ref to list branches and tags.

// Lucas's example: fetching Git branches and tags in parallel

const [branches, tags] = await Promise.all([

$`git for-each-ref --format='%(refname:short)' refs/heads/`.text(),

$`git for-each-ref --format='%(refname:short)' refs/tags/`.text(),

]);At first, I didn't like the idea. Optique's entire API was synchronous, which made it simpler to reason about and avoided the “async infection” problem where one async function forces everything upstream to become async. I argued that shell completion should be near-instantaneous, and if you need async data, you should cache it at startup.

But Lucas pushed back. The filesystem is a database, and many useful completions inherently require async work—Git refs change constantly, and pre-caching everything at startup doesn't scale for large repos. Fair point.

What I needed to solve

So, how do you support both sync and async execution modes in a composable parser library while maintaining type safety?

The key requirements were:

parse()returnsTorPromise<T>complete()returnsTorPromise<T>suggest()returnsIterable<T>orAsyncIterable<T>- When combining parsers, if any parser is async, the combined result must be async

- Existing sync code should continue to work unchanged

The fourth requirement is the tricky one. Consider this:

const syncParser = flag("--verbose");

const asyncParser = option("--branch", asyncValueParser);

// What's the type of this?

const combined = object({ verbose: syncParser, branch: asyncParser });The combined parser should be async because one of its fields is async. This means we need type-level logic to compute the combined mode.

Five design options

I explored five different approaches, each with its own trade-offs.

Option A: conditional types with mode parameter

Add a mode type parameter to Parser and use conditional types:

type Mode = "sync" | "async";

type ModeValue<M extends Mode, T> = M extends "async" ? Promise<T> : T;

interface Parser<M extends Mode, TValue, TState> {

parse(context: ParserContext<TState>): ModeValue<M, ParserResult<TState>>;

// ...

}The challenge is computing combined modes:

type CombineModes<T extends Record<string, Parser<any, any, any>>> =

T[keyof T] extends Parser<infer M, any, any>

? M extends "async" ? "async" : "sync"

: never;Option B: mode parameter with default value

A variant of Option A, but place the mode parameter first with a default

of "sync":

interface Parser<M extends Mode = "sync", TValue, TState> {

readonly $mode: M;

// ...

}The default value maintains backward compatibility—existing user code keeps working without changes.

Option C: separate interfaces

Define completely separate Parser and AsyncParser interfaces with

explicit conversion:

interface Parser<TValue, TState> { /* sync methods */ }

interface AsyncParser<TValue, TState> { /* async methods */ }

function toAsync<T, S>(parser: Parser<T, S>): AsyncParser<T, S>;Simpler to understand, but requires code duplication and explicit conversions.

Option D: union return types for suggest() only

The minimal approach. Only allow suggest() to be async:

interface Parser<TValue, TState> {

parse(context: ParserContext<TState>): ParserResult<TState>; // always sync

suggest(context: ParserContext<TState>, prefix: string):

Iterable<Suggestion> | AsyncIterable<Suggestion>; // can be either

}This addresses the original use case but doesn't help if async parse() is

ever needed.

Option E: fp-ts style HKT simulation

Use the technique from fp-ts to simulate Higher-Kinded Types:

interface URItoKind<A> {

Identity: A;

Promise: Promise<A>;

}

type Kind<F extends keyof URItoKind<any>, A> = URItoKind<A>[F];

interface Parser<F extends keyof URItoKind<any>, TValue, TState> {

parse(context: ParserContext<TState>): Kind<F, ParserResult<TState>>;

}The most flexible approach, but with a steep learning curve.

Testing the idea

Rather than commit to an approach based on theoretical analysis, I created a prototype to test how well TypeScript handles the type inference in practice. I published my findings in the GitHub issue:

Both approaches correctly handle the “any async → all async” rule at the type level. (…) Complex conditional types like

ModeValue<CombineParserModes<T>, ParserResult<TState>>sometimes require explicit type casting in the implementation. This only affects library internals. The user-facing API remains clean.

The prototype validated that Option B (explicit mode parameter with default) would work. I chose it for these reasons:

- Backward compatible: The default

"sync"keeps existing code working - Explicit: The mode is visible in both types and runtime (via a

$modeproperty) - Debuggable: Easy to inspect the current mode at runtime

- Better IDE support: Type information is more predictable

How CombineModes works

The CombineModes type computes whether a combined parser should be sync or

async:

type CombineModes<T extends readonly Mode[]> = "async" extends T[number]

? "async"

: "sync";This type checks if "async" is present anywhere in the tuple of modes.

If so, the result is "async"; otherwise, it's "sync".

For combinators like object(), I needed to extract modes from parser

objects and combine them:

// Extract the mode from a single parser

type ParserMode<T> = T extends Parser<infer M, unknown, unknown> ? M : never;

// Combine modes from all values in a record of parsers

type CombineObjectModes<T extends Record<string, Parser<Mode, unknown, unknown>>> =

CombineModes<{ [K in keyof T]: ParserMode<T[K]> }[keyof T][]>;Runtime implementation

The type system handles compile-time safety, but the implementation also needs

runtime logic. Each parser has a $mode property that indicates its execution

mode:

const syncParser = option("-n", "--name", string());

console.log(syncParser.$mode); // "sync"

const asyncParser = option("-b", "--branch", asyncValueParser);

console.log(asyncParser.$mode); // "async"Combinators compute their mode at construction time:

function object<T extends Record<string, Parser<Mode, unknown, unknown>>>(

parsers: T

): Parser<CombineObjectModes<T>, ObjectValue<T>, ObjectState<T>> {

const parserKeys = Reflect.ownKeys(parsers);

const combinedMode: Mode = parserKeys.some(

(k) => parsers[k as keyof T].$mode === "async"

) ? "async" : "sync";

// ... implementation

}Refining the API

Lucas suggested an important refinement during our

discussion. Instead of having run() automatically choose between sync and

async based on the parser mode, he proposed separate functions:

Perhaps

run(…)could be automatic, andrunSync(…)andrunAsync(…)could enforce that the inferred type matches what is expected.

So we ended up with:

run(): automatic based on parser moderunSync(): enforces sync mode at compile timerunAsync(): enforces async mode at compile time

// Automatic: returns T for sync parsers, Promise<T> for async

const result1 = run(syncParser); // string

const result2 = run(asyncParser); // Promise<string>

// Explicit: compile-time enforcement

const result3 = runSync(syncParser); // string

const result4 = runAsync(asyncParser); // Promise<string>

// Compile error: can't use runSync with async parser

const result5 = runSync(asyncParser); // Type error!I applied the same pattern to parse()/parseSync()/parseAsync() and

suggest()/suggestSync()/suggestAsync() in the facade functions.

Creating async value parsers

With the new API, creating an async value parser for Git branches looks like this:

import type { Suggestion } from "@optique/core/parser";

import type { ValueParser, ValueParserResult } from "@optique/core/valueparser";

function gitRef(): ValueParser<"async", string> {

return {

$mode: "async",

metavar: "REF",

parse(input: string): Promise<ValueParserResult<string>> {

return Promise.resolve({ success: true, value: input });

},

format(value: string): string {

return value;

},

async *suggest(prefix: string): AsyncIterable<Suggestion> {

const { $ } = await import("bun");

const [branches, tags] = await Promise.all([

$`git for-each-ref --format='%(refname:short)' refs/heads/`.text(),

$`git for-each-ref --format='%(refname:short)' refs/tags/`.text(),

]);

for (const ref of [...branches.split("\n"), ...tags.split("\n")]) {

const trimmed = ref.trim();

if (trimmed && trimmed.startsWith(prefix)) {

yield { kind: "literal", text: trimmed };

}

}

},

};

}Notice that parse() returns Promise.resolve() even though it's synchronous.

This is because the ValueParser<"async", T> type requires all methods to use

async signatures. Lucas pointed out this is a minor ergonomic issue. If only

suggest() needs to be async, you still have to wrap parse() in a Promise.

I considered per-method mode granularity (e.g., ValueParser<ParseMode, SuggestMode, T>), but the implementation complexity would multiply

substantially. For now, the workaround is simple enough:

// Option 1: Use Promise.resolve()

parse(input) {

return Promise.resolve({ success: true, value: input });

}

// Option 2: Mark as async and suppress the linter

// biome-ignore lint/suspicious/useAwait: sync implementation in async ValueParser

async parse(input) {

return { success: true, value: input };

}What it cost

Supporting dual modes added significant complexity to Optique's internals. Every combinator needed updates:

- Type signatures grew more complex with mode parameters

- Mode propagation logic had to be added to every combinator

- Dual implementations were needed for sync and async code paths

- Type casts were sometimes necessary in the implementation to satisfy TypeScript

For example, the object() combinator went from around 100 lines to around

250 lines. The internal implementation uses conditional logic based on the

combined mode:

if (combinedMode === "async") {

return {

$mode: "async" as M,

// ... async implementation with Promise chains

async parse(context) {

// ... await each field's parse result

},

};

} else {

return {

$mode: "sync" as M,

// ... sync implementation

parse(context) {

// ... directly call each field's parse

},

};

}This duplication is the cost of supporting both modes without runtime overhead for sync-only use cases.

Lessons learned

Listen to users, but validate with prototypes

My initial instinct was to resist async support. Lucas's persistence and concrete examples changed my mind, but I validated the approach with a prototype before committing. The prototype revealed practical issues (like TypeScript inference limits) that pure design analysis would have missed.

Backward compatibility is worth the complexity

Making "sync" the default mode meant existing code continued to work

unchanged. This was a deliberate choice. Breaking changes should require

user action, not break silently.

Unified mode vs per-method granularity

I chose unified mode (all methods share the same sync/async mode) over

per-method granularity. This means users occasionally write

Promise.resolve() for methods that don't actually need async, but the

alternative was multiplicative complexity in the type system.

Designing in public

The entire design process happened in a public GitHub issue. Lucas, Giuseppe,

and others contributed ideas that shaped the final API. The

runSync()/runAsync() distinction came directly from Lucas's feedback.

Conclusion

This was one of the more challenging features I've implemented in Optique. TypeScript's type system is powerful enough to encode the “any async means all async” rule at compile time, but getting there required careful design work and prototyping.

What made it work: conditional types like ModeValue<M, T> can bridge the gap

between sync and async worlds. You pay for it with implementation complexity,

but the user-facing API stays clean and type-safe.

Optique 0.9.0 with async support is currently in pre-release testing. If you'd like to try it, check out PR #70 or install the pre-release:

npm add @optique/core@0.9.0-dev.212 @optique/run@0.9.0-dev.212

deno add --jsr @optique/core@0.9.0-dev.212 @optique/run@0.9.0-dev.212Feedback is welcome!

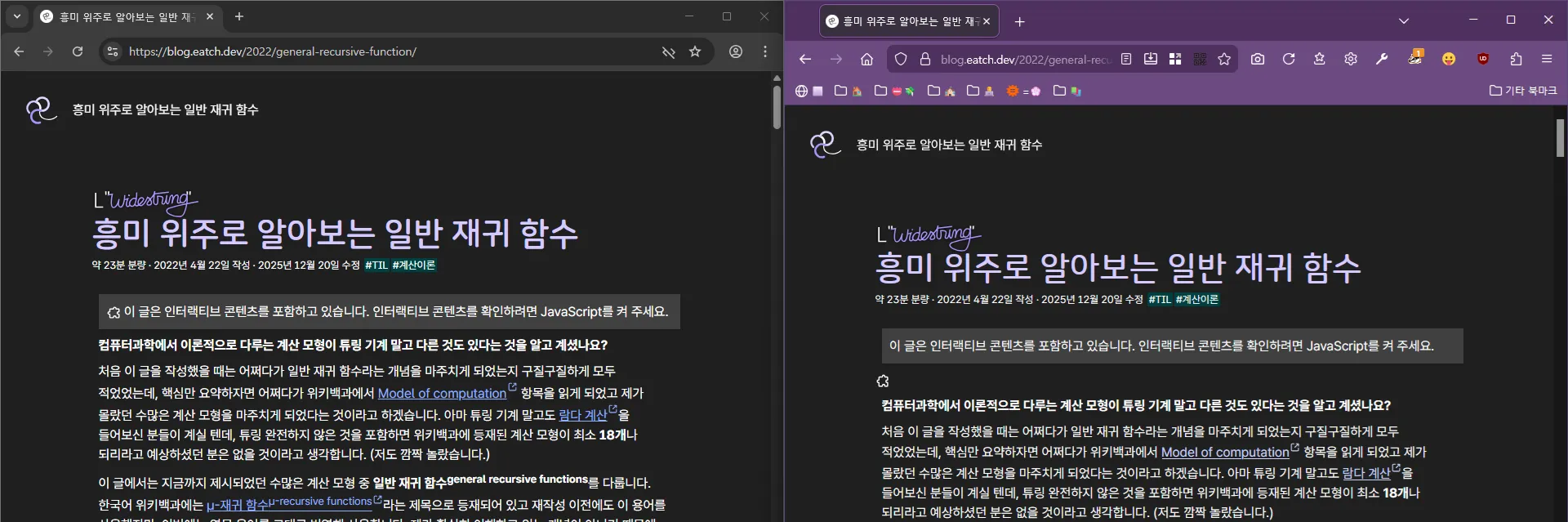

(오프라인에서 했던 얘기를 온라인에서도 하기) ![]() @hongminhee洪 民憙 (Hong Minhee) 님 블로그는 국한문혼용으로 보면 세로쓰기 가로스크롤로 바뀌는 게 꽤나 운치가 있다고 생각해요..... 한자를 못 읽는 건 아쉽지만

@hongminhee洪 民憙 (Hong Minhee) 님 블로그는 국한문혼용으로 보면 세로쓰기 가로스크롤로 바뀌는 게 꽤나 운치가 있다고 생각해요..... 한자를 못 읽는 건 아쉽지만

ProseMirror 꽤 재밌네....

세상의 발전이란건 참 빠르구나... 라는 생각이 새삼 들었어요 한 30년쯤 전에는 프로그램이 메모리와 장치에 직접 접근할 수 있었고 협조 안 해주면 혼자서 CPU를 다 먹을 수 있는 시대가 있었다는게 믿기지 않지 않아요??

TIL: <form>에 .submit()을 하면 이벤트를 거치지 않고 검증도 안하고 냅다 제출이 된다. 이벤트를 거치게 만들려면 .requestSubmit()을 해야 된다

Just had someone leave feedback on my F/OSS project saying “maybe that's fine if a product is focused on your Chinese community.”

I'm Korean. Every single piece of documentation is in English. There's nothing in Chinese anywhere in the project.

This kind of microaggression is exhausting. As a non-white maintainer, you deal with these assumptions constantly—people who feel entitled to your labor while casually othering you based on your name.

It chips away at your motivation. It makes you wonder why you bother.

https://github.com/dahlia/optique/issues/59#issuecomment-3678606022

제 지인 분이 GitHub 에서 인종차별적 코멘트를 받으셨습니다. GitHub 계정이 있으시면 신고 부탁드립니다. 영어가 어려우시더라도 LLM으로 신고글 써달라고 하면 잘 써줍니다. 신고는 단 시간 내에 많이 찍혀야 실제 보고로 올라가기 때문에 가능하신 분들은 꼭 신고 부탁드립니다.

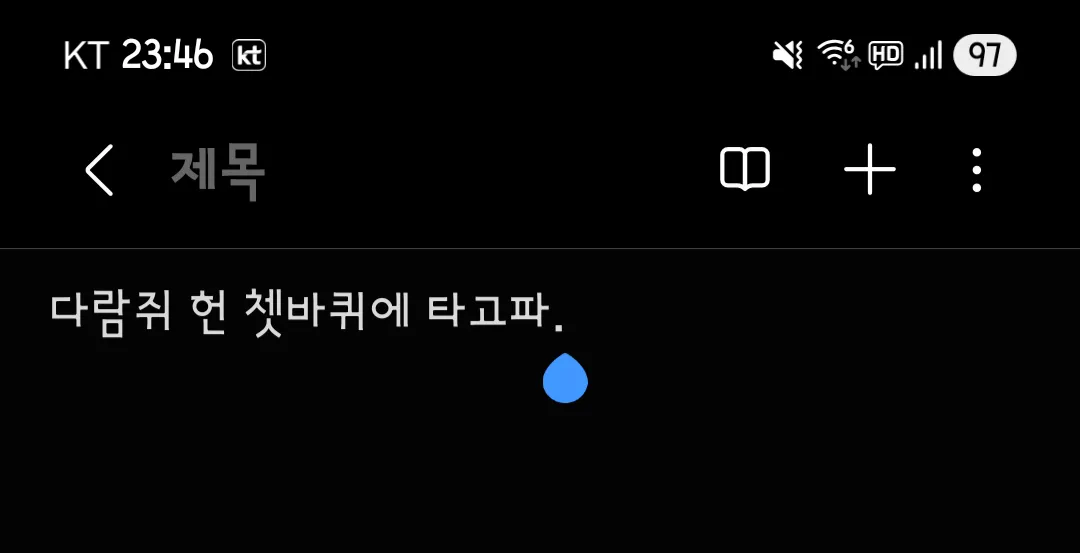

여러분!!! 모바일에서 텍스트 편집을 할 때 나오는 저 '파란색 그거'를 뭐라고 하나요???

여러분!!! 모바일에서 텍스트 편집을 할 때 나오는 저 '파란색 그거'를 뭐라고 하나요???

해결했어요!

「Text Selection Handle」

루비(Ruby)의 홈페이지가 새 단장했다고 해서 들어가봤는데 꽤 예쁜데? https://www.ruby-lang.org/ko/

![]() @gaeulbyul가을별 오 우연찮게 오늘 들어갈 일이 있었는데 일주일도 안된 따끈한 리뉴얼이었군요...

@gaeulbyul가을별 오 우연찮게 오늘 들어갈 일이 있었는데 일주일도 안된 따끈한 리뉴얼이었군요...

루비(Ruby)의 홈페이지가 새 단장했다고 해서 들어가봤는데 꽤 예쁜데? https://www.ruby-lang.org/ko/

ㅠㅠㅠㅠㅠㅠㅠㅠ

@eatch잇창명 EatChangmyeong💕🐱 텍스트 커서(text cursor) 내지는 캐럿(caret)이라고 부르는 걸로 아는데… 이걸 궁금해 하신 게 아니려나요?

![]() @hongminhee洪 民憙 (Hong Minhee) 앗 저는 깜박이는 | 말고 그 밑에 나오는 💧 이게 궁금했던 거라서요.......🥺

@hongminhee洪 民憙 (Hong Minhee) 앗 저는 깜박이는 | 말고 그 밑에 나오는 💧 이게 궁금했던 거라서요.......🥺

여러분!!! 모바일에서 텍스트 편집을 할 때 나오는 저 '파란색 그거'를 뭐라고 하나요???

파이어폭스 버그인지는 모르겠는데 <noscript> 안에 깊숙이 들어가있는 <span>이 밖으로 빠져나온다

왜냐면 이 글을 재작성하고 있고 인터랙티브 부분이 복잡해서 타입 안정성은 웬만하면 챙기고 싶은데 타입스크립트도 안되고 ReScript도 안되고 굳이 Idris를 가져다 쓰는 건 오버킬같고...

많은 우여곡절이 있었지만 어쨌든 해냈습니다. 내일 배포해야지

When code is more complex than it needs to be, its under-engineered, not over

I was wondering when browsers started calling the UI "chrome" (it's not a Google thing!)

Amazingly, the Firefox (then Mozilla) commit that introduced the "chrome" tree into the source code dates back to Sep 4, 1998... which is also the same day Google was founded!

Edit: Netscape used the term much earlier though! Not as much in filenames, but in the actual source code it's all over the place.

Calling all #fediverse developers for help: I'm currently trying to implement a #reporting (#flag) feature for Hackers' Pub, an #ActivityPub-enabled community for software engineers. Is there a formal specification for how cross-instance reporting should work in ActivityPub? Or, is there any well-documented material that explains how the major implementations handle it?

리디에서 마크다운 이벤트를 할 때마다 **이 markdown**인 줄 알고 당황하는 사람

왜요??????

아 DM으로 보냈어야 되는데 공개설정 잘못했다

🏃➡️

혹시 해커스펍에는 신고 기능이 없나요....?? 행동강령에서는 분명 있다고 하는데

문맥적으로 알아서 어떤 타입이어야 하는지 추론해주는 정적 분석기가 달린 언어는 없나

언제까지 (a:number, b:number) => a + b, (a:string, b:string) => a + b, <T>(a: T, b: T) => a + b 를 해줘야 하나고

그냥 대충 눈치껏 (a, b) => a + b 하면 'b 는 a 와 더할 수 있어야 하는 타입이고 a 는 무언가와 더할 수 있는 타입이구나' 하고 추론할 수 있는 분석기가 달린 언어가 필요함

갑자기 삘이 와서 블로그 리팩토링을 한참 했고 이제 각주에도 수식을 쓸 수 있다!!

어떻게 구현했길래 수식을 못 썼냐고요??

- (before)

.mdx파일에 별도 익스포트로 각주 내용을 썼었는데 왠지모르게 JSX 문법은 되지만 마크다운 문법은 안 되는 상황에 봉착... Astro가 별도 익스포트를 못 봐서import.global.meta로 불러오고 원래는 볼 일 없는AstroVNode타입을 써가면서 온몸비틀기로 구현 - (after) 모든 각주가 별도 파일(🤣).

import.global.meta는 아직 있지만 고치기 전보다 훨씬 깔끔해진 느낌

갑자기 삘이 와서 블로그 리팩토링을 한참 했고 이제 각주에도 수식을 쓸 수 있다!!

JS 프레임워크 성격테스트도 있네 😂

I'm Solid! You're the performance-obsessed perfectionist! Take the quiz to find your JS framework match! js-framework-quiz.vercel.app/result/solid

I'm Solid!

![Claude 웹 인터페이스에서 parent_message_uuid: Input should be a valid UUID, invalid character: expected an optional prefix of `urn:uuid:` followed by [0-9a-fA-F-], found `n` at 1 오류가 발생했다.](https://media.hackers.pub/note-media/13f91565-e130-454b-8453-669d3bf978d8.webp)

![* 21. Ba5# - 백이 룩과 퀸을 희생한 후, 퀸 대신 **비숍(Ba5)**이 결정적인 체크메이트를 성공시킵니다. 흑 킹이 탈출할 곳이 없으며, 백의 기물로 막을 수도 없습니다. [강조 처리된 "비숍(Ba5)" 앞뒤에 마크다운의 강조 표시 "**"가 그대로 노출되어 있다.]](https://media.hackers.pub/note-media/17646c5d-3f9d-472b-9d56-dd34006ad291.webp)