洪 民憙 (Hong Minhee)

@hongminhee@hackers.pub · 1019 following · 725 followers

Hi, I'm who's behind Fedify, Hollo, BotKit, and this website, Hackers' Pub! My main account is at ![]() @hongminhee洪 民憙 (Hong Minhee)

@hongminhee洪 民憙 (Hong Minhee)  .

.

Fedify, Hollo, BotKit, 그리고 보고 계신 이 사이트 Hackers' Pub을 만들고 있습니다. 제 메인 계정은: ![]() @hongminhee洪 民憙 (Hong Minhee)

@hongminhee洪 民憙 (Hong Minhee)  .

.

Fedify、Hollo、BotKit、そしてこのサイト、Hackers' Pubを作っています。私のメインアカウントは「![]() @hongminhee洪 民憙 (Hong Minhee)

@hongminhee洪 民憙 (Hong Minhee)  」に。

」に。

Website

- hongminhee.org

GitHub

- @dahlia

Hollo

- @hongminhee@hollo.social

DEV

- @hongminhee

velog

- @hongminhee

Qiita

- @hongminhee

Zenn

- @hongminhee

Matrix

- @hongminhee:matrix.org

X

- @hongminhee

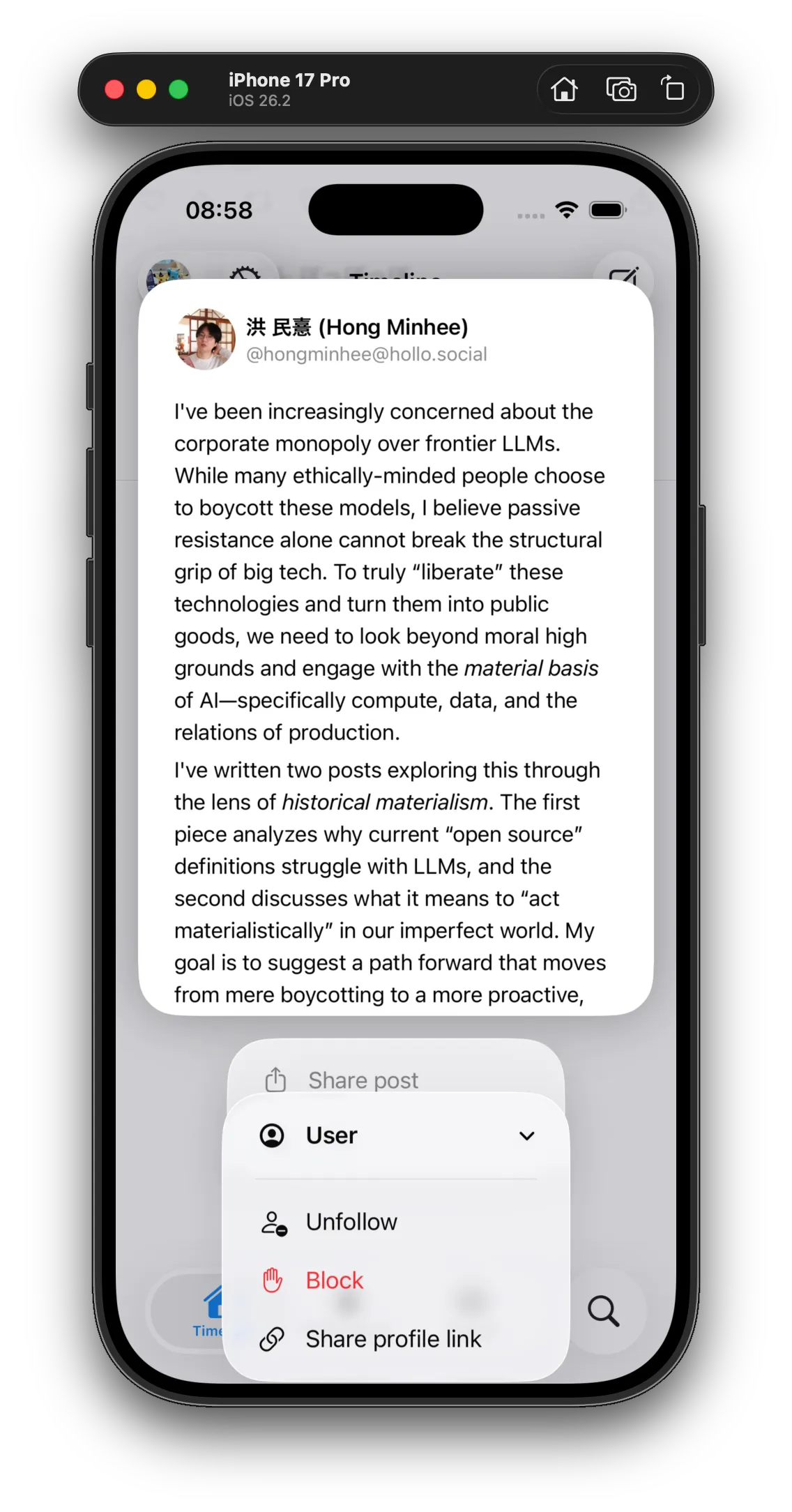

![]() 洪 民憙 (Hong Minhee) shared the below article:

洪 民憙 (Hong Minhee) shared the below article:

Nix Store에서 언어의 특권적 지위 제거: Sandbox 기반 아키텍처 제안

bgl gwyng @bgl@hackers.pub

Nix 아키텍처에서 Nix 언어가 스토어(store)에 대해 가지는 특권적 지위와 그로 인한 생태계 종속성 문제를 짚어보고, 이를 해결하기 위한 샌드박스(sandbox) 기반의 구조적 개선안을 제안합니다. 핵심은 언어의 순수성에 의존하던 기존의 신뢰 모델을 OS 레벨의 격리와 데몬(daemon) 프로토콜로 전환하는 것입니다. 이러한 변화를 통해 Nix 언어뿐만 아니라 파이썬(Python)이나 러스트(Rust) 등 다양한 언어가 동등한 지위에서 스토어와 상호작용할 수 있게 되며, 빌드와 평가의 경계를 허물어 더욱 유연하고 견고한 시스템을 구축할 수 있는 통찰을 제공합니다.

Read more →jemalloc이 archive 되었던 것 같은데 unarchive하고 다시 작업을 이어간다네요

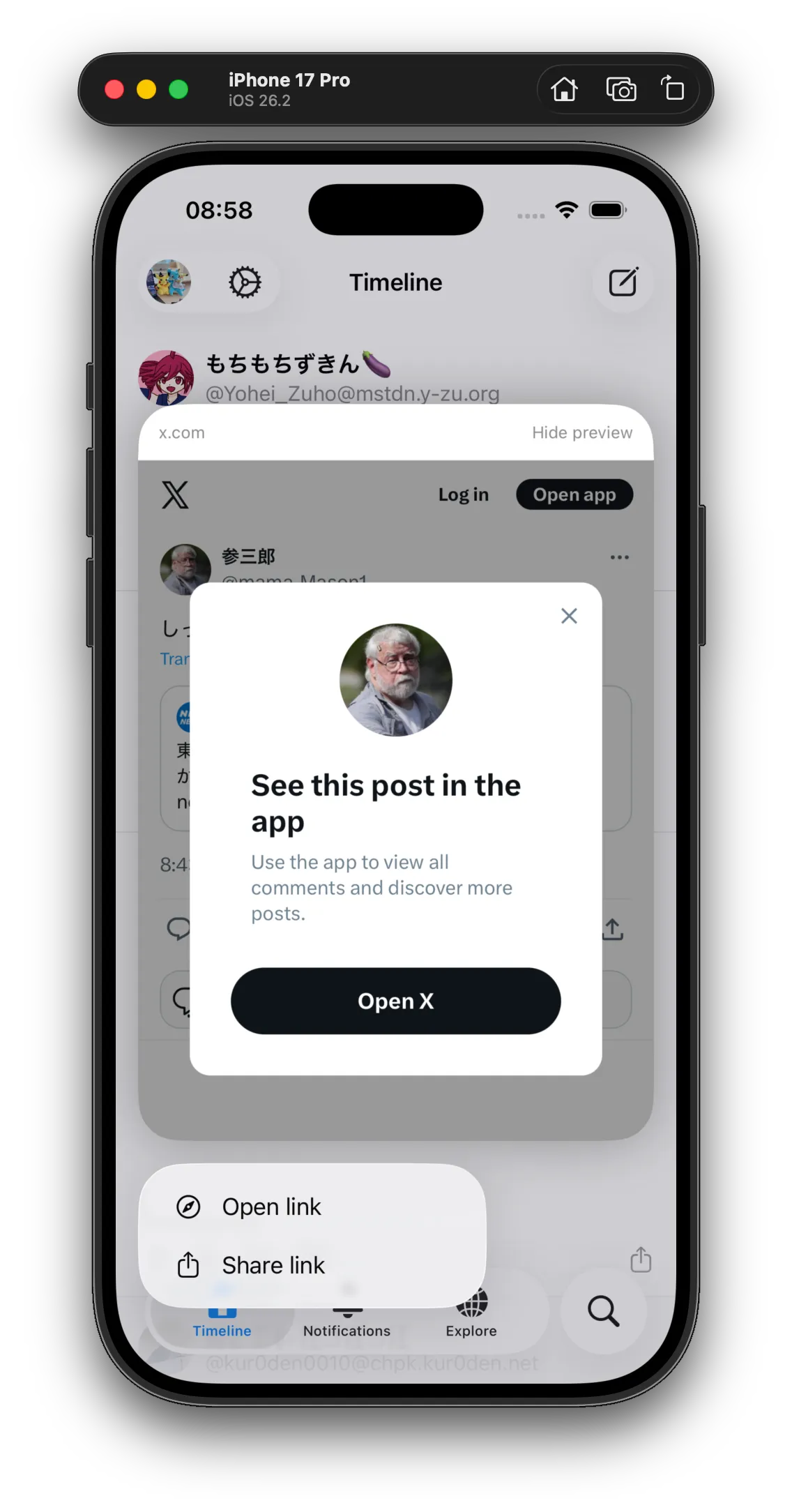

이제 web-next보다 iOS 앱이 기능 더 많다… 😂

연휴 끝나고 업무 시작하기 전에 Sneak Peak까지 구현했다. 뿌-듯

요즘 같은 시대에 의식적으로 (남에게도 나에게도) 하려는 말은 “과로하지 말라”는 것이다.

4개월만 지나면 만2년차 개발자인가 시간 참 빠르다

-----BEGIN PGP SIGNED MESSAGE----- Hash: SHA512

안녕하세요. 기존 개인 마스토돈 서버(![]() @litehell)를 폐쇄하고 조만간 다음 계정들을 주로 이용하려 합니다.

@litehell)를 폐쇄하고 조만간 다음 계정들을 주로 이용하려 합니다.

계획은 위와 같다만 실제로 어떻게 될 지는 모르겠네요. 암튼 잘 부탁드립니다~ -----BEGIN PGP SIGNATURE-----

iQEzBAEBCgAdFiEE1nk3aDhvWQyStq+HxUHmBcRhj0wFAmmlqJYACgkQxUHmBcRh j0yxAQgAqQrAB79GkO3FgvbwzrGZKyDNqjjLxyG5dd++557PHXcQLXPAdy9YQpDr tRC6IR1VmAS08blHC5jNYfrk5xypDr3lKmfquxaLyIv+cICv5RWkrIjutiR8oQHl 7HONcinGCZinGdcKjvLVMuYGogGtTvS2lFLITDA4yYSvnpEvwZPqqc8alqplMdYh REyJeIcPehGzw69jYC13tFqyprn9L7PyZEabvpcnHlX1BELE3yhXLXY+QfkVHo1z zdrUpL/f68G9nSZ7ZNwq0w6TfWXtCj3hTRmG669jU6nbWDwRg5mQ4cLN9c4Ms498 0B5jHhsic7pHwOa5XknugRp2s1fnbw== =jITN -----END PGP SIGNATURE-----

台湾のg0v summit 2026の早割チケットが明日3/3の現地時間10時から販売開始らしい。

シビックテックを最近知った、かつ内向的な人間が個人としていきなり海外カンファレンスに参加するのは勇気がいるけど、もうチケット買っちゃって退路を塞ごうかな…!

https://g0v.social/@summit/116157874383012918

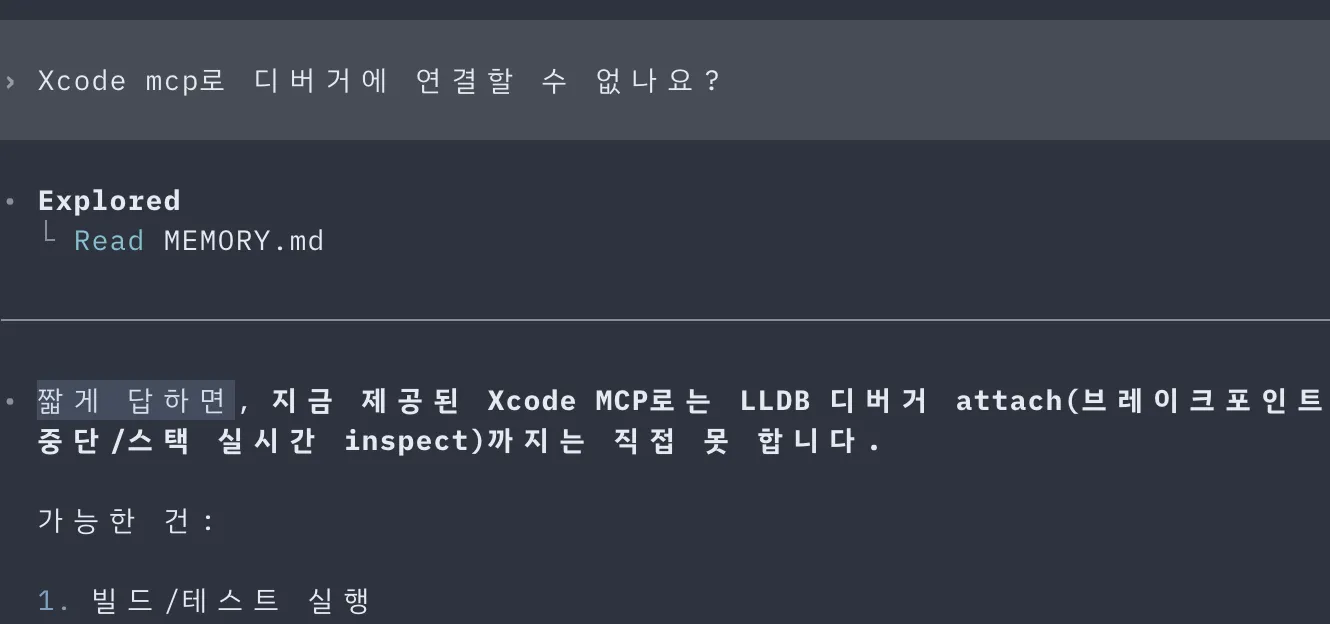

코딩하다가 막혀서 클로드한테 물어보려고 프롬프트를 짜고 있으면 문득 뭐가 문제인지 보여서 쓰던 프롬프트를 버리고 그냥 인간지능으로 고치는 일이 자주 생긴다...

ㄴ 너 방금 러버덕 디버깅을 발명했어

그 뭐시냐.... 제가 모임 개최 플랫폼 (대충 https://event-us.kr 혹은 https://connpass.com 같은거) + 지역 기반 리뷰 서비스 (대충 포스퀘어 같은거) 를 만들었는데요.

**당연히, 연합우주 거주민 대상으로 만들어진 서비스이고, 연합우주에 계정이 있다면 누구나 OTP 로그인으로 인증이 가능합니다**

어떻게 만들어나갈지 나름 고민은 많이 해봤고, 내가 생각하는 고민이랑 다른 사람들이 생각하는 수요가 일치하는지 확인도 하고 싶어서 이렇게 공개적인 글을 올립니다.

많은 관심과 사랑 부탁드리고, 문의사항이나 피드백 있으면 GitHub Issue로 부탁드리겠습니다. GitHub 링크 : https://github.com/moim-social/moim

물론, 다른 창구도 열어둘 여지는 있습니다. 디스코드 채널은.. 당장은 https://fedidev.kr 의 #moim 채널을 이용하지 않을까 싶구요.

LLM 코딩 에이전트가 좋다 신기하다 노래를 부르는 것도 하루이틀이지… 어째서 다들 그 똑같은 얘기를 길고 길고 길게 풀어서 여기에서도 말하고 저기에서도 말하고 그러는 걸까?

오랜만입니다. 근황 겸...

2월 말 퇴사했습니다. 역시 Web3는 제가 "잘" 하는거지 "좋아" 하진 않는 것 같습니다. 평가도 좋고 계속 할 수도 있었지만 뭔가 이젠 시들해지기도 했고, 원래부터 Web3로 커리어를 잡으려고 했던 것도 아니라서 다음 직장을 알아봤습니다.

그래서 4월 1일부터 크레페(쿠키플레이스)로 옮깁니다. 김민상(bis_cir_kit) 님 추천으로 지원하게 되었는데, 타입으로 그래프 나타내는 건 원래 좋아하던 일이라서 스택도 잘 맞고, 회사 감성도 완전 찰떡이라 일주일 만에 합류 결정이 되었습니다.

그 사이엔 결혼 일정때문에 바빴습니다. 3월 7일에 대구에서 결혼합니다. 너무 멀어서 미안한 나머지 청첩장은 많이 못 돌렸지만 이렇게나마 소식은 전합니다.

wedding.suho.io 에서 저희 사진과 정보를 더 확인하실 수 있습니다.

또한 2월 중순쯤 퇴사가 확정되고 나서 만들고 있는 프로젝트가 있습니다. whaleback.suho.io 입니다. 한국 주식을 각 종목별로 퀀트 분석해 주고, AI 리포트로 일간 트렌드를 알려주는 등, 각종 정보를 보기 편하게 정리했습니다.

사용해 보시고 궁금한 점 있거나, 아니면 저 개인이 궁금하시더라도 연락주세요. 감사합니다.

![]() @bin_bash_shell이수호 결혼도 축하드리고, 이직도 축하드려요!

@bin_bash_shell이수호 결혼도 축하드리고, 이직도 축하드려요!

오랜만입니다. 근황 겸...

2월 말 퇴사했습니다. 역시 Web3는 제가 "잘" 하는거지 "좋아" 하진 않는 것 같습니다. 평가도 좋고 계속 할 수도 있었지만 뭔가 이젠 시들해지기도 했고, 원래부터 Web3로 커리어를 잡으려고 했던 것도 아니라서 다음 직장을 알아봤습니다.

그래서 4월 1일부터 크레페(쿠키플레이스)로 옮깁니다. 김민상(bis_cir_kit) 님 추천으로 지원하게 되었는데, 타입으로 그래프 나타내는 건 원래 좋아하던 일이라서 스택도 잘 맞고, 회사 감성도 완전 찰떡이라 일주일 만에 합류 결정이 되었습니다.

그 사이엔 결혼 일정때문에 바빴습니다. 3월 7일에 대구에서 결혼합니다. 너무 멀어서 미안한 나머지 청첩장은 많이 못 돌렸지만 이렇게나마 소식은 전합니다.

wedding.suho.io 에서 저희 사진과 정보를 더 확인하실 수 있습니다.

또한 2월 중순쯤 퇴사가 확정되고 나서 만들고 있는 프로젝트가 있습니다. whaleback.suho.io 입니다. 한국 주식을 각 종목별로 퀀트 분석해 주고, AI 리포트로 일간 트렌드를 알려주는 등, 각종 정보를 보기 편하게 정리했습니다.

사용해 보시고 궁금한 점 있거나, 아니면 저 개인이 궁금하시더라도 연락주세요. 감사합니다.

AI 에이전트의 신뢰성 측정 방법을 제안하는 연구. 기존 에이전트 벤치마크가 평균 성공률에만 치중했기 때문에 평가 결과가 좋아도 실제 환경에서는 자주 실패함을 지적한다. 에이전트가 얼마나 일관되게 동작하는지, 환경 변화에 얼마나 버티는지, 실패를 예측할 수 있는지, 오류가 얼마나 심각한지 알기 위해서는 정확성이 아닌 신뢰성을 평가해야 한다는 것이다. https://hal.cs.princeton.edu/reliability/

ChatGPT가 한국어로 "너 **핵심을 찔렀어"같이 말하는 것처럼 일본어에선 結論から言うと(결론부터 말하자면)로 시작하는 경우가 많다고 한다.

그리고 지금 내 Codex 세션이 딱 그런 느낌으로 응답하고 있네...

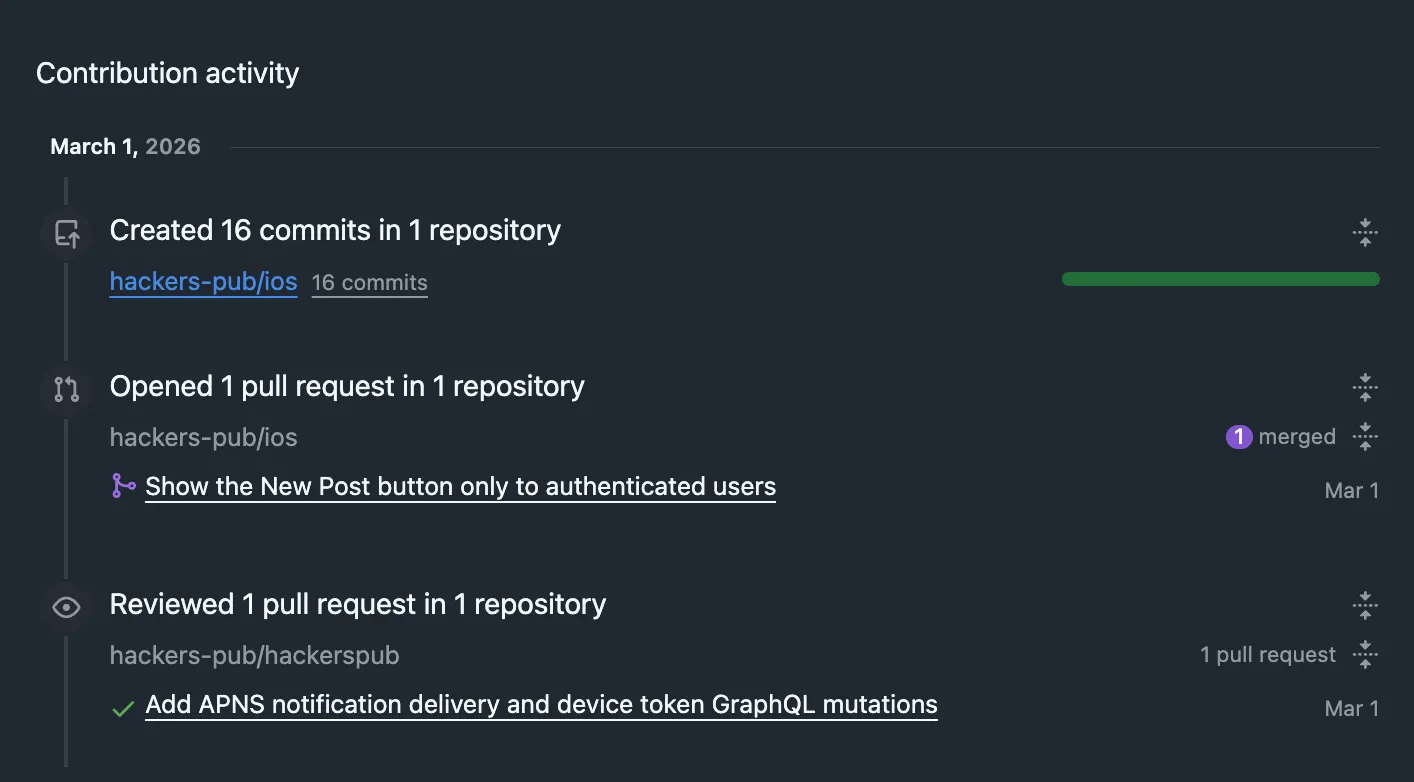

오늘 하루 Hackers Pub iOS 앱에 작업한 것들

- 긴 글을 잘라서 보여줄 때 HTML truncate할 때 HTML 태그 구조에 이상이 없게끔 안전하게 처리

- 글 리스트 보여줄 때 렌더링 최적화

- 글 리스트 / 상세 페이지에서 인용된 글도 제대로 보이도록 수정하고 인용 기능 추가

- 글에 반응하기 기능 추가

- 누가 글을 공유하거나 인용했는지 화면 추가

조금만 더 하면... 앱스토어 올려도 되겠다...

I've been saying for a while that we need something like FediCon in East Asia. A dedicated conference is still a stretch, but I've been thinking about a smaller step:

![]() @COSCUP 2026 (Taipei, Aug 8–9) is accepting proposals for community tracks. It might be worth trying to open a Social Web track there—something in the spirit of the Social Web devroom at FOSDEM.

@COSCUP 2026 (Taipei, Aug 8–9) is accepting proposals for community tracks. It might be worth trying to open a Social Web track there—something in the spirit of the Social Web devroom at FOSDEM.

Nothing is decided yet, but if you're working on #ActivityPub, the #fediverse, or anything in the social web space and might be interested in speaking (or co-organizing), I'd love to hear from you.

東아시아에도 FediCon 같은 行事가 있으면 좋겠다는 말을 여러 番 해왔는데요. 獨立的인 컨퍼런스는 아직 어렵더라도, 작은 첫걸음으로 생각해보고 있는 게 있습니다.

![]() @COSCUP 2026(臺北, 8月 8日–9日)이 커뮤니티 트랙 提案을 받고 있어요. FOSDEM의 Social Web devroom 같은 느낌으로, 거기서 Social Web 트랙을 열 수 있지 않을까 하고 構想 중입니다.

@COSCUP 2026(臺北, 8月 8日–9日)이 커뮤니티 트랙 提案을 받고 있어요. FOSDEM의 Social Web devroom 같은 느낌으로, 거기서 Social Web 트랙을 열 수 있지 않을까 하고 構想 중입니다.

아직 確定된 건 아무것도 없지만, #ActivityPub, #聯合宇宙, 或은 소셜 웹 全般을 다루고 있고 發表나 共同 오거나이징에 關心이 있으신 분이 있다면 이야기 걸어주세요.

I would like to migrate some of my projects to Codeberg, but since Codeberg doesn't seem to support PyPI's Trusted Publishing (yet), I don't think I'll be able to do that...

대만의 국제적 오픈 소스 컨퍼런스인 COSCUP 2026의 CFP 공모가 떴습니다! 혹시 발표를 하거나 부스를 내보고 싶으신 분 계실까요?

🚀 COSCUP 2026 Call for Participation is now open!

🎤 Community Tracks – Run a open-source agenda with talks, panels, or workshops. Apply by Mar 23. Spots are limited.

🛠 Community Booths – Showcase your project, recruit members, and connect. Apply by Jun 9. First come, first served.

👉 Apply here: https://s.coscup.org/26communityen

스택오버플로우 로고 이상해졌어

아... Emacs 정도의 확장성에 Zed 정도의 성능에 VS Code 정도의 까리함을 모두 갖는 에디터 어디 없나...

튜링의사과 오픈런하러감 끼얏호우~

개발자로서 느끼는 Nix의 최대장점은 패키지가 가능한한 최대로 configurable하다는 것이다. 가령 nixpkgs와 homebrew에 똑같이 10만개의 패키지가 있다고 하자. 하지만 nixpkgs에는 실제로 그보다 훨씬 많은 수의 패키지가 있는 셈이다. 저 10만개 외에도, 쉽게 설정을 바꿔서 안전하게 새로 빌드할수 있는 잠재적인 패키지들이 무수히 많기 때문이다.

요즘 일할 때 Opus 4.6보다 GPT-5.3 Codex를 애용하고 있지만 그럼에도 나는 Anthropic이 LLM의 alignment나 safety, explainability 분야에서 제일 잘 하고 있는 곳이라고 생각한다.

미국 정부와 관련된 일련의 사건에서 누가 잘잘못을 따지는 것과는 별개로 미국 정부가 저렇게까지 강경하게 나서서 가지지 못하면 부숴버리겠어!!!!!! 같은 스탠스를 취하고 있다는건, 그만큼 Anthropic의 모델이 우수해서가 아닐까.

그러고선 OpenAI가 Anthropic 자리를 대신 들어갔는데 정작 OpenAI도 Anthropic가 제한한걸 그대로 제한하고도 계약을 딴걸 보면 미국 정부가 자기네 정치적 이유로 OpenAI를 밀어줬거나 OpenAI는 미국 정부가 원하는 것을 이루기 위해 뒤에서 제한을 풀어주지 않을까하는 우려가 크다.

모델 선호에 대해 조금 더 말하자면 여전히 문서를 작성히거나 이미지가 필요 없는 모든 작업에선 Claude를 선호한다. 코딩 작업 시 planning과 review 단계에서 Codex를 훨씬 더 선호하고, 코드를 작성하거나 수정하는 일은 토큰 효율이나 시간 효율을 생각하면 Opus나 Sonnet이 더 좋다.

요즘 일할 때 Opus 4.6보다 GPT-5.3 Codex를 애용하고 있지만 그럼에도 나는 Anthropic이 LLM의 alignment나 safety, explainability 분야에서 제일 잘 하고 있는 곳이라고 생각한다.

미국 정부와 관련된 일련의 사건에서 누가 잘잘못을 따지는 것과는 별개로 미국 정부가 저렇게까지 강경하게 나서서 가지지 못하면 부숴버리겠어!!!!!! 같은 스탠스를 취하고 있다는건, 그만큼 Anthropic의 모델이 우수해서가 아닐까.

그러고선 OpenAI가 Anthropic 자리를 대신 들어갔는데 정작 OpenAI도 Anthropic가 제한한걸 그대로 제한하고도 계약을 딴걸 보면 미국 정부가 자기네 정치적 이유로 OpenAI를 밀어줬거나 OpenAI는 미국 정부가 원하는 것을 이루기 위해 뒤에서 제한을 풀어주지 않을까하는 우려가 크다.

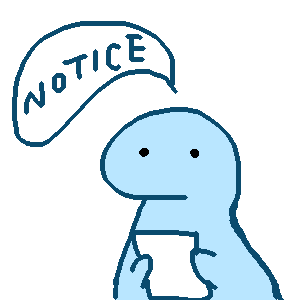

Jiwon (![]() @z9mb1Jiwon), one of our core contributors, drew a Fedify dino! How cute!

@z9mb1Jiwon), one of our core contributors, drew a Fedify dino! How cute!

https://oeee.cafe/@z9mb1/2b5b0baf-466b-4c65-a1e0-d3588f0666f4

Fedify dino for notice

https://kre.pe/CKwN This is a paid request :) fediverse logo was attached afterwards.

@moim.liveMoim 를 해커스펍 못지않게 Fedify의 어지간한 기능을 지원하는 방향으로 개발하는 것이 목표....

써놓고보니 성수역 근처가 아니고 뚝섬역 근처 ㅋㅋ!!!

![]() @kodingwarriorJaeyeol Lee 수정 기능도 만드셔야겠네요 ㅋㅋㅋ

@kodingwarriorJaeyeol Lee 수정 기능도 만드셔야겠네요 ㅋㅋㅋ

2026년 튜링의 사과 할일

튜링의 사과 평일 SNS 모니터링 가동.

마스트돈에서도 꾸준히 활동 하기!

TIL: MDX를 쓸 때 <a href="https://example.com">테스트</a>처럼 태그 밖에 텍스트가 하나도 없으면 <p>로 감싸주지 않는다 (의도는 알겠는데 그래도 왜?)

Instead of using git as a database, what if you used database as a git?

I making auto-translated FEP document for Japanese, trying local models...

아오... gha버려야지 컨테이너 쓰는 경우 뭐 재사용 기능이 멀쩡한게 없네

beelink 미니PC를 주문했다. NixOS, Tvix, LLM 에이전트를 가지고 놀아보려고 한다.

[🍏매장안내]

튜링의 사과 키보드 타건 배치를 변경하였습니다.

브랜드별로 한쪽 공간에 배치하여 체험하실 수 있도록 구비 해놨습니다.

미니 해커톤, 무료 강연등 다양하고 알찬 프로그램 준비해보고자합니다. 언제든지 협업 문의가 있으시다면 연락주세요! 많은 관심 부탁드립니다.

튜링의 사과팀의 2026년 다양한 활동 기대해주세요!😄

日本かアジア圏でActivityPubとかオープンデータとかシビックテックのカンファレンスやイベントがあればちょっとずつ参加していきたいな。英語もまた話せるように鍛え直さないと…

シビックテックで取り組んでる課題をチームの皆で話してて、データはJSON-LDで記述したほうが良さそうとか、いずれシェア機能が欲しいねとか、コンテンツはオープンデータ化を前提としてデータの帰属は市民や地域コミュニティとしたいね等々を話し合う中で、「なんか…ActivityPub感…」と思った。

ActivityPubをオープンデータの流通・蓄積・活用の際に用いている取り組みとかって、あるのかな?

Open GLAMなどでありそうな気もするけど、どうなんだろ。

앗! 나도 해커스펍 기여자? Hackers Pub 기여자 모임 스프린트

Hackers' Pub 리뉴얼, 손꼽아 기다리고 계시지 않으신가요? Hackers' Pub, 한 번쯤 직접 기여해 보고 싶다는 생각, 해보신 적 없으신가요? Hackers' Pub, 이용하면서 어딘가 아쉽다 느꼈던 부분, 혹시 있지 않으셨나요? 이번 스프린트 모임은 리뉴얼 진도도 팍팍 빼면서, 기여자들끼리 서로 얼굴도 익히고 친분도 쌓는 자리입니다. 부담 없이 참여해 주세요. 모임은 서울특별시 성동구 상원길 26, 뚝섬역 5번 출구 근처 어딘가에 있는 튜링의 사과에서 진행합니다. 일정은 3월 1일 ~ 3월 2일. 모여서 각자 편하게 해커스펍 기여하다가 가시면 됩니다. 몸만 오시면 됩니다. 비용은 튜링의 사과 이용료만 챙겨 주시면 돼요. 감사합니다. 이 글은 연합우주를 위한 모임 개최 서비스 moim.live의 첫 게시글로 영광스럽게 공유합니다

📅 2026-03-01T02:00:00.000Z — 2026-03-02T10:00:00.000Z

Organized by: @hongminhee@hollo.social

앗! 나도 해커스펍 기여자? Hackers Pub 기여자 모임 스프린트 — Hackers' Pub (@hackerspub@moim.live)

Hackers' Pub 리뉴얼, 손꼽아 기다리고 계시지 않으신가요? Hackers' Pub, 한 번쯤 직접 기여해 보고 싶다는 생각, 해보신 적 없으신가요? Hackers' Pub, 이용하면서 어딘가 아쉽다 느꼈던 부분, 혹시 있지 않으셨나요? 이번 스프린트 모임은 리뉴얼 진도도 팍팍 빼면서, 기여자들끼리 서로 얼굴도 익히고 친분도 쌓는 자리입니다. 부담 없이 참여해 주세요. 모임은 서울특별시 성동구 상원길 26, 뚝섬역 5번 출구 근처 어딘가에 있는 튜링의 사과에서 진행합니다. 일정은 3월 1일 ~ 3월 2일. 모여서 각자 편하게 해커스펍 기여하다가 가시면 됩니다. 몸만 오시면 됩니다. 비용은 튜링의 사과 이용료만 챙겨 주시면 돼요. 감사합니다. 이 글은 연합우주를 위한 모임 개최 서비스 moim.live의 첫 게시글로 영광스럽게 공유합니다

moim.live

Link author: ![]() Hackers' Pub@hackerspub@moim.live

Hackers' Pub@hackerspub@moim.live

Starting with Deno 2.7, you can now use the Temporal API without the --unstable-temporal flag!

회사에 프론트엔드 포지션이 예상치 못하게 공석이 되어 진정한 풀스택으로 거듭나게 되었다. 다행히 중요한 것들은 구현이 마무리되서 코드 정리만 좀 하면 될 듯

나는 한 사람이 AI로 일주일만에 만들었다는게 소구점이 되는지 잘 모르겠다 https://blog.cloudflare.com/vinext/

지난주 Astro를 인수한 클플이 Next.js를 조롱하기 위해 만들었다는 의견이 그럴듯해보임

나는 한 사람이 AI로 일주일만에 만들었다는게 소구점이 되는지 잘 모르겠다 https://blog.cloudflare.com/vinext/