며칠 전 Fedify에 팬아웃을 두 단계로 나누는 변경을 통해 Hackers' Pub에서 단문 작성시 오래 걸리는 문제를 해결했었는데 (그래봤자 팔로워가 100명이 넘는 나한테나 느낄 수 있는 문제였을 것 같지만), 이렇게 하니까 큐에서 팬아웃 태스크 자체가 오랫동안 안 빠지는 체증이 존재해서 큐에 여러 메시지를 넣는 연산 자체를 새로 추가하고 있다. 정확히는 PostgreSQL을 큐로 사용하고 있는데, 메시지 하나 넣고 NOTIFY하고, 다음 메시지 넣고 또 NOTIFY하고… 하는 게 비효율적이라 메시지를 일단 다 넣은 다음 NOTIFY를 한 번만 하도록 고치고 있다.

XiNiHa

@xiniha@hackers.pub · 91 following · 112 followers

GitHub

- @XiNiHa

Bluesky

- @xiniha.dev

Twitter

- @xiniha_1e88df

Fedify 쪽의 MessageQueue 인터페이스에 선택적인 enqueueMany() 연산을 추가했고, @fedify/postgres 패키지에서도 해당 연산을 구현했다. Hackers' Pub에 적용했고, 이제 효과가 있는지 두고 보면 된다…

XiNiHa shared the below article:

Bluesky는 X의 훌륭한 대안일 수 있지만, 연합우주의 대안은 아닙니다

洪 民憙 (Hong Minhee) @hongminhee@hackers.pub

최근 X(구 Twitter)를 떠나는 사용자들이 늘면서 Bluesky에 대한 관심이 높아지고 있습니다. Bluesky는 깔끔한 인터페이스와 과거 Twitter와 유사한 사용자 경험을 제공하며, '신뢰할 수 있는 이탈'이라는 매력적인 개념을 내세워 X의 유력한 대안으로 떠오르고 있습니다. 하지만 이 글에서는 Bluesky와 그 기반 프로토콜인 AT Protocol이 연합우주(fediverse)의 대안이 될 수 없는 이유를 설명합니다. Bluesky는 메시지 전달 방식 대신 공유 힙 방식을 사용하며, 이는 중앙 릴레이에 의존하게 만들어 탈중앙화의 이상과는 거리가 멀어집니다. 또한, 전역 뷰에 대한 집착은 차단 목록의 전체 공개와 같은 개인 정보 보호 문제를 야기하며, AT Protocol은 아직 특정 사기업에 의해 주도되고 있어 개방형 표준으로서의 한계를 가지고 있습니다. Bluesky는 이동 가능한 아이덴티티를 제공하지만, 여전히 중앙화된 요소에 의존하고 있으며, DM은 완전히 중앙화되어 있습니다. 결론적으로, Bluesky는 X의 훌륭한 대안이 될 수 있지만, 연합우주가 제공하는 탈중앙화된 가치와 경험을 대체하기는 어려울 것입니다. 이 글을 통해 Bluesky와 연합우주의 차이점을 명확히 이해하고, 자신에게 맞는 플랫폼을 선택하는 데 도움이 될 것입니다.

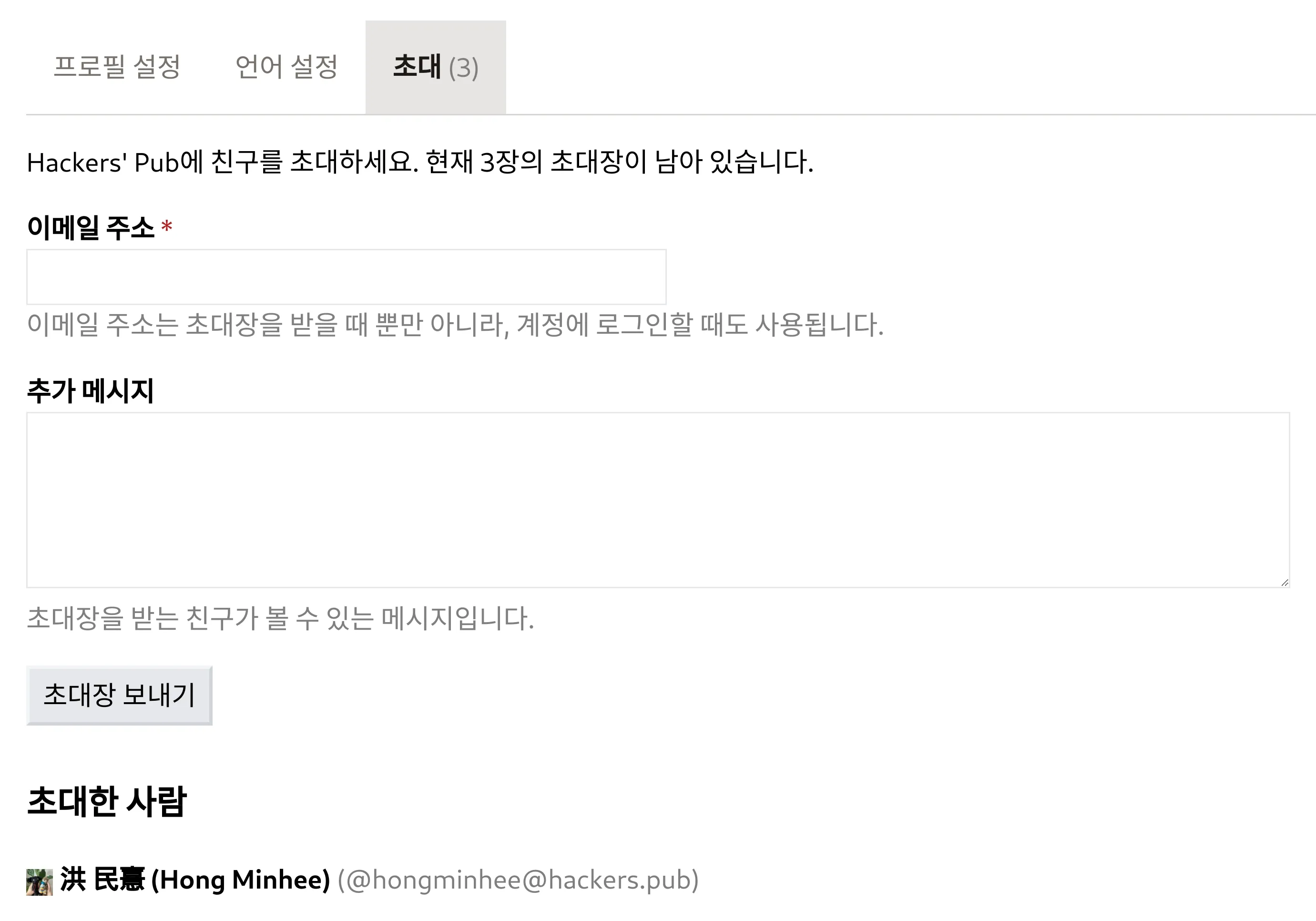

Read more →📢 Hackers' Pub 초대 시스템 오픈!

Hackers' Pub에 초대 시스템이 적용되었습니다. 이제 설정 → 초대 페이지에서 지인들을 초대할 수 있습니다.

주요 내용:

- 초대장 3장 지급: 기존 회원분들께 3장의 초대장이 지급되었습니다.

- 초대 방법: 설정 → 초대 페이지에서 초대 링크를 생성하여 공유하거나, 이메일 주소를 입력하여 초대할 수 있습니다.

- 추가 초대: 초대장은 향후 비정기적으로 추가될 예정입니다.

- 자동 팔로: 초대자와 피초대자는 자동으로 상호 팔로됩니다. (언팔로 가능.)

Hackers' Pub의 퀄리티를 유지하고, 더욱 풍성한 기술 논의를 위해 신중한 초대를 부탁드립니다.

궁금한 점이나 건의사항은 답글로 남겨주세요.

Hackers' Pub 커뮤니티 성장에 많은 참여 부탁드립니다!

![]() @curry박준규 확장이 하도 많아서 뭐가 있는지 다 알기가 어려운 것 같아요… 😂

@curry박준규 확장이 하도 많아서 뭐가 있는지 다 알기가 어려운 것 같아요… 😂

![]() @hongminhee洪 民憙 (Hong Minhee) 이런 표현이 있습니다.

@hongminhee洪 民憙 (Hong Minhee) 이런 표현이 있습니다.

GHC has more flags than the UN.

XiNiHa shared the below article:

Revisiting Java's Checked Exceptions: An Underappreciated Type Safety Feature

洪 民憙 (Hong Minhee) @hongminhee@hackers.pub

Despite their bad reputation in the Java community, checked exceptions provide superior type safety comparable to Rust's Result<T, E> or Haskell's Either a b—we've been dismissing one of Java's best features all along.

Introduction

Few features in Java have been as consistently criticized as checked exceptions. Modern Java libraries and frameworks often go to great lengths to avoid them. Newer JVM languages like Kotlin have abandoned them entirely. Many experienced Java developers consider them a design mistake.

But what if this conventional wisdom is wrong? What if checked exceptions represent one of Java's most forward-thinking features?

In this post, I'll argue that Java's checked exceptions were ahead of their time, offering many of the same type safety benefits that are now celebrated in languages like Rust and Haskell. Rather than abandoning this feature, we should consider how to improve it to work better with modern Java's features.

Understanding Java's Exception Handling Model

To set the stage, let's review how Java's exception system works:

-

Unchecked exceptions (subclasses of

RuntimeExceptionorError): These don't need to be declared or caught. They typically represent programming errors (NullPointerException,IndexOutOfBoundsException) or unrecoverable conditions (OutOfMemoryError). -

Checked exceptions (subclasses of

Exceptionbut notRuntimeException): These must either be caught withtry/catchblocks or declared in the method signature withthrows. They represent recoverable conditions that are outside the normal flow of execution (IOException,SQLException).

Here's how this works in practice:

// Checked exception - compiler forces you to handle or declare it

public void readFile(String path) throws IOException {

Files.readAllLines(Path.of(path));

}

// Unchecked exception - no compiler enforcement

public void processArray(int[] array) {

int value = array[array.length + 1]; // May throw ArrayIndexOutOfBoundsException

}The Type Safety Argument for Checked Exceptions

At their core, checked exceptions are a way of encoding potential failure modes into the type system via method signatures. This makes certain failure cases part of the API contract, forcing client code to explicitly handle these cases.

Consider this method signature:

public byte[] readFileContents(String filePath) throws IOExceptionThe throws IOException clause tells us something critical: this method might fail in ways related to IO operations. The compiler ensures you can't simply ignore this fact. You must either:

- Handle the exception with a try-catch block

- Propagate it by declaring it in your own method signature

This type-level representation of potential failures aligns perfectly with principles of modern type-safe programming.

Automatic Propagation: A Hidden Advantage

One often overlooked advantage of Java's checked exceptions is their automatic propagation. Once you declare a method as throws IOException, any exception that occurs is automatically propagated to the caller without additional syntax.

Compare this with Rust, where you must use the ? operator every time you call a function that returns a Result:

// Rust requires explicit propagation with ? for each call

fn read_and_process(path: &str) -> Result<(), std::io::Error> {

let content = std::fs::read_to_string(path)?;

process_content(&content)?;

Ok(())

}

// Java automatically propagates exceptions once declared

void readAndProcess(String path) throws IOException {

String content = Files.readString(Path.of(path));

processContent(content); // If this throws IOException, it's automatically propagated

}In complex methods with many potential failure points, Java's approach leads to cleaner code by eliminating the need for repetitive error propagation markers.

Modern Parallels: Result Types in Rust and Haskell

The approach of encoding failure possibilities in the type system has been adopted by many modern languages, most notably Rust with its Result<T, E> type and Haskell with its Either a b type.

In Rust:

fn read_file_contents(file_path: &str) -> Result<Vec<u8>, std::io::Error> {

std::fs::read(file_path)

}When calling this function, you can't just ignore the potential for errors—you need to handle both the success case and the error case, often using the ? operator or pattern matching.

In Haskell:

readFileContents :: FilePath -> IO (Either IOException ByteString)

readFileContents path = try $ BS.readFile pathAgain, the caller must explicitly deal with both possible outcomes.

This is fundamentally the same insight that motivated Java's checked exceptions: make failure handling explicit in the type system.

Valid Criticisms of Checked Exceptions

If checked exceptions are conceptually similar to these widely-praised error handling mechanisms, why have they fallen out of favor? There are several legitimate criticisms:

1. Excessive Boilerplate in the Call Chain

The most common complaint is the boilerplate required when propagating exceptions up the call stack:

void methodA() throws IOException {

methodB();

}

void methodB() throws IOException {

methodC();

}

void methodC() throws IOException {

// Actual code that might throw IOException

}Every method in the chain must declare the same exception, creating repetitive code. While automatic propagation works well within a method, the explicit declaration in method signatures creates overhead.

2. Poor Integration with Functional Programming

Java 8 introduced lambdas and streams, but checked exceptions don't play well with them:

// Won't compile because map doesn't expect functions that throw checked exceptions

List<String> fileContents = filePaths.stream()

.map(path -> Files.readString(Path.of(path))) // Throws IOException

.collect(Collectors.toList());This forces developers to use awkward workarounds:

List<String> fileContents = filePaths.stream()

.map(path -> {

try {

return Files.readString(Path.of(path));

} catch (IOException e) {

throw new UncheckedIOException(e); // Wrap in an unchecked exception

}

})

.collect(Collectors.toList());3. Interface Evolution Problems

Adding a checked exception to an existing method breaks all implementing classes and calling code. This makes evolving interfaces over time difficult, especially for widely-used libraries and frameworks.

4. Catch-and-Ignore Anti-Pattern

The strictness of checked exceptions can lead to the worst possible outcome—developers simply catching and ignoring exceptions to make the compiler happy:

try {

// Code that might throw

} catch (Exception e) {

// Do nothing or just log

}This is worse than having no exception checking at all because it provides a false sense of security.

Improving Checked Exceptions Without Abandoning Them

Rather than abandoning checked exceptions entirely, Java could enhance the existing system to address these legitimate concerns. Here are some potential improvements that preserve the type safety benefits while addressing the practical problems:

1. Allow lambdas to declare checked exceptions

One of the biggest pain points with checked exceptions today is their incompatibility with functional interfaces. Consider how much cleaner this would be:

// Current approach - forced to handle or wrap exceptions inline

List<String> contents = filePaths.stream()

.map(path -> {

try {

return Files.readString(Path.of(path));

} catch (IOException e) {

throw new RuntimeException(e);

}

})

.collect(Collectors.toList());

// Potential future approach - lambdas can declare exceptions

List<String> contents = filePaths.stream()

.map((String path) throws IOException -> Files.readString(Path.of(path)))

.collect(Collectors.toList());This would require updating functional interfaces to support exception declarations:

@FunctionalInterface

public interface Function<T, R, E extends Exception> {

R apply(T t) throws E;

}2. Generic exception types in throws clauses

Another powerful enhancement would be allowing generic type parameters in throws clauses:

public <E extends Exception> void processWithException(Supplier<Void, E> supplier) throws E {

supplier.get();

}This would enable much more flexible composition of methods that work with different exception types, bringing some of the flexibility of Rust's Result<T, E> to Java's existing exception system.

3. Better support for exception handling in functional contexts

Unlike Rust which requires the ? operator for error propagation, Java already automatically propagates checked exceptions when declared in the method signature. What Java needs instead is better support for checked exceptions in functional contexts:

// Current approach for handling exceptions in streams

List<String> contents = filePaths.stream()

.map(path -> {

try {

return Files.readString(Path.of(path));

} catch (IOException e) {

throw new RuntimeException(e); // Lose type information

}

})

.collect(Collectors.toList());

// Hypothetical improved API

List<String> contents = filePaths.stream()

.mapThrowing(path -> Files.readString(Path.of(path))) // Preserves checked exception

.onException(IOException.class, e -> logError(e))

.collect(Collectors.toList());4. Integration with Optional<T> and Stream<T> APIs

The standard library could be enhanced to better support operations that might throw checked exceptions:

// Hypothetical API

Optional<String> content = Optional.ofThrowable(() -> Files.readString(Path.of("file.txt")));

content.ifPresentOrElse(

this::processContent,

exception -> log.error("Failed to read file", exception)

);Comparison with Other Languages' Approaches

It's worth examining how other languages have addressed the error handling problem:

Rust's Result<T, E> and ? operator

Rust's approach using Result<T, E> and the ? operator shows how propagation can be made concise while keeping the type safety benefits. The ? operator automatically unwraps a successful result or returns the error to the caller, making propagation more elegant.

However, Rust's approach requires explicit propagation at each step, which can be more verbose than Java's automatic propagation in certain scenarios.

Kotlin's Approach

Kotlin made all exceptions unchecked but provides functional constructs like runCatching that bring back some type safety in a more modern way:

val result = runCatching {

Files.readString(Path.of("file.txt"))

}

result.fold(

onSuccess = { content -> processContent(content) },

onFailure = { exception -> log.error("Failed to read file", exception) }

)This approach works well with Kotlin's functional programming paradigm but lacks compile-time enforcement.

Scala's Try[T], Either[A, B], and Effect Systems

Scala offers Try[T], Either[A, B], and various effect systems that encode errors in the type system while integrating well with functional programming:

import scala.util.Try

val fileContent: Try[String] = Try {

Source.fromFile("file.txt").mkString

}

fileContent match {

case Success(content) => processContent(content)

case Failure(exception) => log.error("Failed to read file", exception)

}This approach preserves type safety while fitting well with Scala's functional paradigm.

Conclusion

Java's checked exceptions were a pioneering attempt to bring type safety to error handling. While the implementation has shortcomings, the core concept aligns with modern type-safe approaches to error handling in languages like Rust and Haskell.

Copying Rust's Result<T, E> might seem like the obvious solution, but it would represent a radical departure from Java's established paradigms. Instead, targeted enhancements to the existing checked exceptions system—like allowing lambdas to declare exceptions and supporting generic exception types—could preserve Java's unique approach while addressing its practical limitations.

The beauty of such improvements is that they'd maintain backward compatibility while making checked exceptions work seamlessly with modern Java features like lambdas and streams. They would acknowledge that the core concept of checked exceptions was sound—the problem was in the implementation details and their interaction with newer language features.

So rather than abandoning checked exceptions entirely, perhaps we should recognize them as a forward-thinking feature that was implemented before its time. As Java continues to evolve, we have an opportunity to refine this system rather than replace it.

In the meantime, next time you're tempted to disparage checked exceptions, remember: they're not just an annoying Java quirk—they're an early attempt at the same type safety paradigm that newer languages now implement with much celebration.

What do you think? Could these improvements make checked exceptions viable for modern Java development? Or is it too late to salvage this controversial feature? I'm interested in hearing your thoughts in the comments.

C++ 표준화 위원회(WG21)에게 C++의 원 저자인 비야네 스트롭스트룹Bjarne Stroustrup이 보낸 메일이 이번 달 초에 본인에 의해 공개된 모양이다. C++가 요즘 안전하지 않은 언어라고 열심히 얻어 맞고 있는 게 싫은지 프로파일(P3081)이라고 하는 언어 부분집합을 정의하려고 했는데, 프로파일이 다루는 문제들이 아주 쉬운 것부터 연구가 필요한 것까지 한데 뒤섞여 있어 구현이 매우 까다롭기에 해당 제안이 적절하지 않음을 올해 초에 가멸차게 까는 글(P3586)이 올라 오자 거기에 대한 응답으로 작성된 것으로 보인다. 더 레지스터의 표현을 빌면 "(본지가 아는 한) 스트롭스트룹이 이 정도로 강조해서 말하는 건 2018년 이래 처음"이라나.

여론은 당연히 호의적이지 않은데, 기술적인 반론이 대부분인 P3586과는 달리 해당 메일은 원래 공개 목적이 아니었음을 감안해도 기술적인 얘기는 쏙 빼 놓고 프로파일이 "코드를 안 고치고도 안전성을 가져 갈 수 있다"는 허황된 주장에 기반해 그러니까 프로파일을 당장 집어 넣어야 한다고 주장하고 있으니 그럴 만도 하다. 스트롭스트룹이 그렇게 이름을 언급하지 않으려고 했던 러스트를 굳이 들지 않아도, 애당초 (이 또한 계속 부정하고 싶겠지만) C++의 주요 장점 중 하나였던 강력한 C 호환성이 곧 메모리 안전성의 가장 큰 적이기 때문에 프로파일이 아니라 프로파일 할아버지가 와도 안전성을 진짜로 확보하려면 코드 수정이 필수적이고, 프로파일이 그 문제를 해결한다고 주장하는 건 눈 가리고 아웅이라는 것을 이제는 충분히 많은 사람들이 깨닫지 않았는가. 스트롭스트룹이 허황된 주장을 계속 반복하는 한 C++는 안전해질 기회가 없을 듯 하다.

저는 AI에게 감사 인사를 하는 데에도 돈이 든다는 걸 깨달아버려서, 이제는 감사도 표하지 않는 삭막한 인간이 되고야 말았습니다.

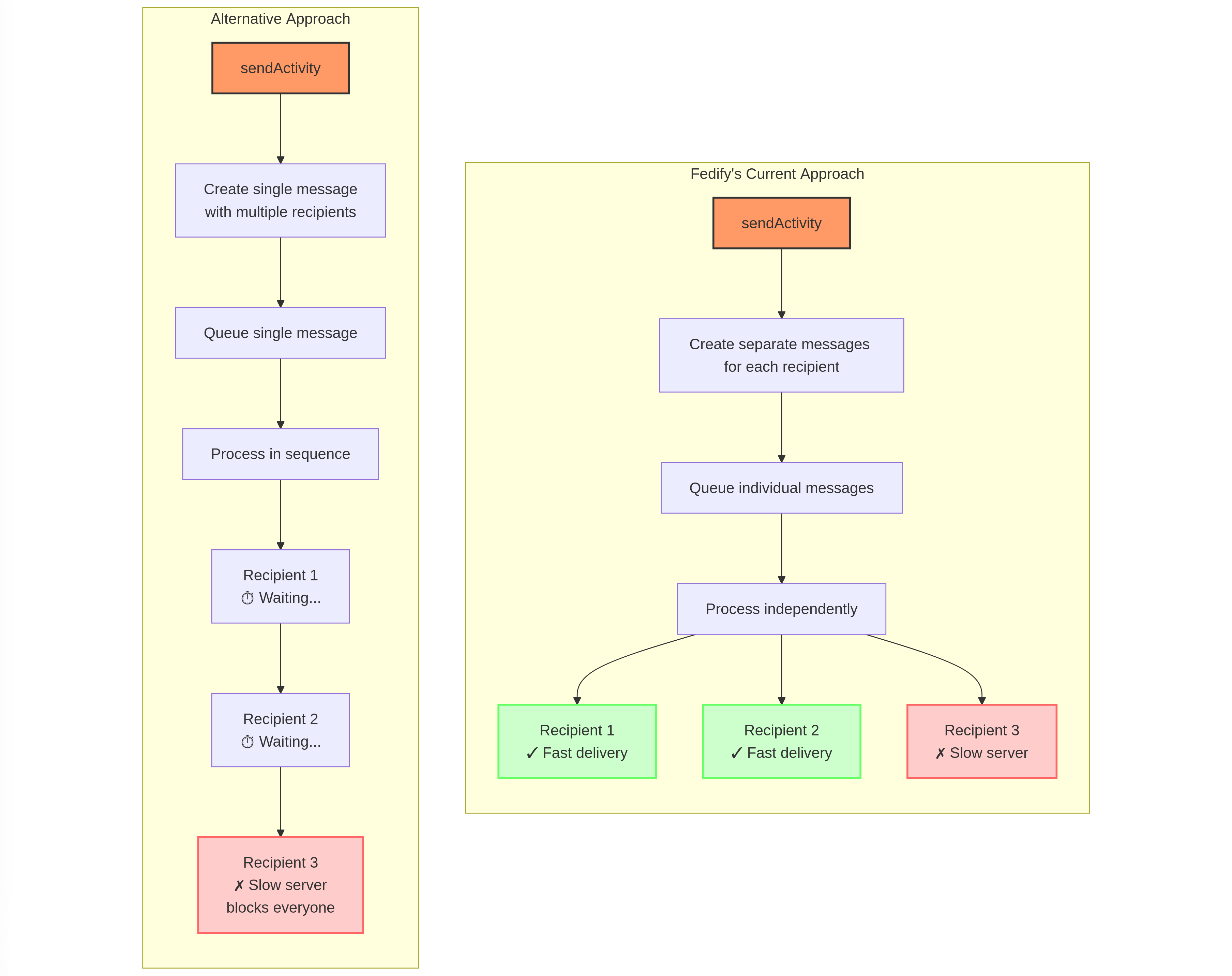

Got an interesting question today about #Fedify's outgoing #queue design!

Some users noticed we create separate queue messages for each recipient inbox rather than queuing a single message and handling the splitting later. There's a good reason for this approach.

In the #fediverse, server response times vary dramatically—some respond quickly, others slowly, and some might be temporarily down. If we processed deliveries in a single task, the entire batch would be held up by the slowest server in the group.

By creating individual queue items for each recipient:

- Fast servers get messages delivered promptly

- Slow servers don't delay delivery to others

- Failed deliveries can be retried independently

- Your UI remains responsive while deliveries happen in the background

It's a classic trade-off: we generate more queue messages, but gain better resilience and user experience in return.

This is particularly important in federated networks where server behavior is unpredictable and outside our control. We'd rather optimize for making sure your posts reach their destinations as quickly as possible!

What other aspects of Fedify's design would you like to hear about? Let us know!

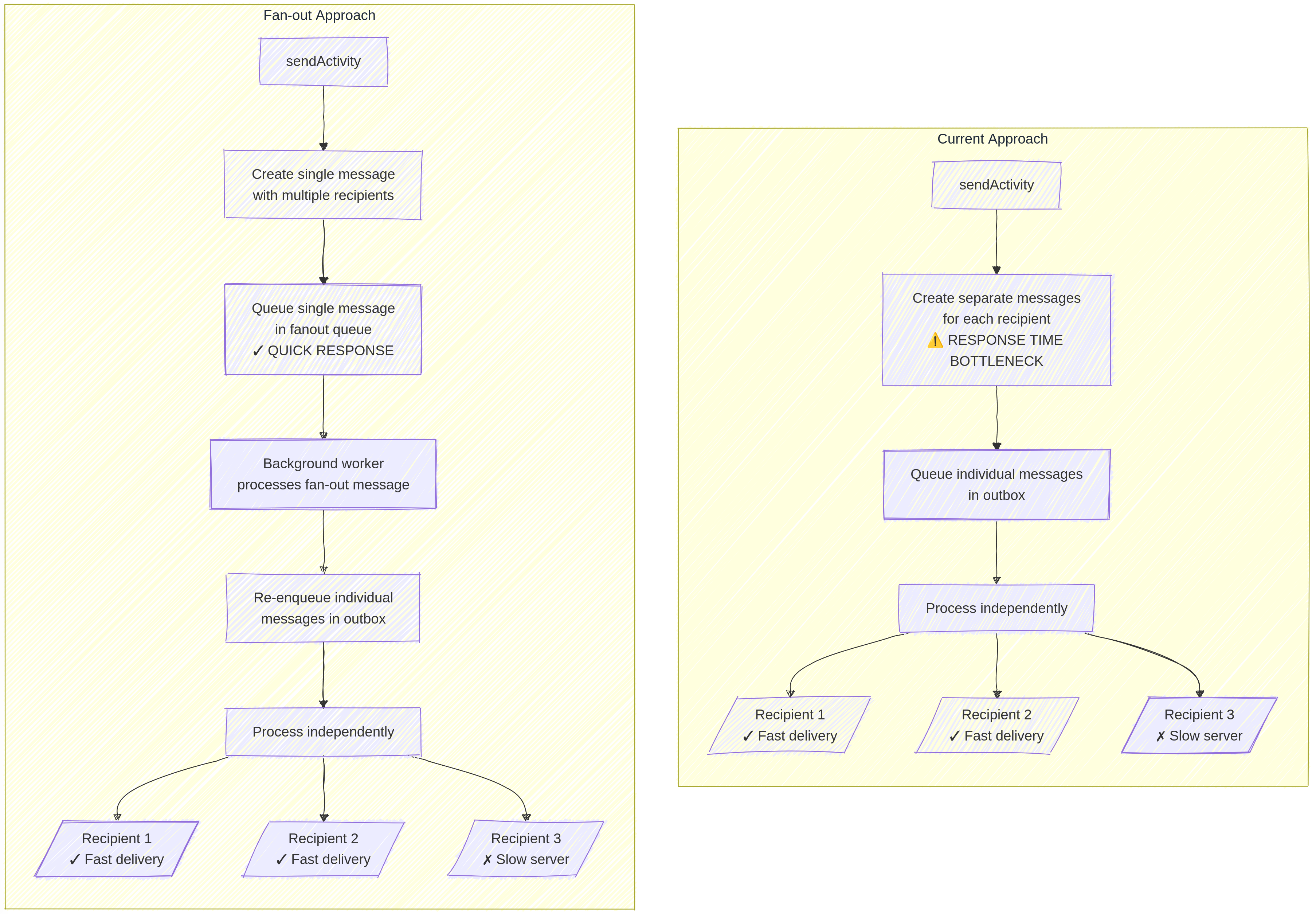

Coming soon in #Fedify 1.5.0: Smart fan-out for efficient activity delivery!

After getting feedback about our queue design, we're excited to introduce a significant improvement for accounts with large follower counts.

As we discussed in our previous post, Fedify currently creates separate queue messages for each recipient. While this approach offers excellent reliability and individual retry capabilities, it causes performance issues when sending activities to thousands of followers.

Our solution? A new two-stage “fan-out” approach:

- When you call

Context.sendActivity(), we'll now enqueue just one consolidated message containing your activity payload and recipient list - A background worker then processes this message and re-enqueues individual delivery tasks

The benefits are substantial:

Context.sendActivity()returns almost instantly, even for massive follower counts- Memory usage is dramatically reduced by avoiding payload duplication

- UI responsiveness improves since web requests complete quickly

- The same reliability for individual deliveries is maintained

For developers with specific needs, we're adding a fanout option with three settings:

"auto"(default): Uses fanout for large recipient lists, direct delivery for small ones"skip": Bypasses fanout when you need different payload per recipient"force": Always uses fanout even with few recipients

// Example with custom fanout setting

await ctx.sendActivity(

{ identifier: "alice" },

recipients,

activity,

{ fanout: "skip" } // Directly enqueues individual messages

);

This change represents months of performance testing and should make Fedify work beautifully even for extremely popular accounts!

For more details, check out our docs.

What other #performance optimizations would you like to see in future Fedify releases?

Mastodon이나 Misskey 등에서 민감한 내용으로 지정한 단문의 내용이나 첨부 이미지는 이제 Hackers' Pub에서 뿌옇게 보이게 됩니다. 마우스 커서를 가져다 대면 또렷하게 보이게 됩니다. 다만, Hackers' Pub에서 쓰는 단문을 민감한 내용으로 지정하는 기능은 없습니다. (아마도 앞으로도 없을 것 같습니다.)

XiNiHa shared the below article:

rel="me" 메모

Lee Dogeon @moreal@hackers.pub

Hackers' Pub의 프로필 링크 인증 기능이 제대로 작동하지 않아, GitHub 링크를 추가했음에도 체크 표시가 나타나지 않는 문제를 해결하기 위한 여정을 담고 있습니다. `rel="me"` 속성이 HTML 링크 요소에서 어떤 역할을 하는지 MDN 문서를 통해 알아보고, GitHub 프로필 설정에서 Hackers' Pub 링크를 추가할 때 `rel="me"` 속성이 자동으로 추가되는 것을 확인합니다. Hackers' Pub의 오픈 소스 코드를 분석하여 인증 마크가 표시되는 과정을 파악하고, GitHub에 Hackers' Pub 링크를 추가한 후 프로필 설정을 다시 저장하면 인증 체크 표시가 나타나는 것을 확인합니다. 이 글은 `rel="me"` 속성의 역할과 Hackers' Pub의 링크 인증 과정을 이해하고, 문제 해결 방법을 제시하여 독자들이 유사한 문제를 겪을 때 도움을 받을 수 있도록 합니다.

Read more →사람들이 잘 모르는 Markdown 명세 하나. CommonMark, 즉 표준 Markdown에서 URL은 자동으로 링크되지 않는다. 대부분의 Markdown 구현체들이 이를 옵션으로 지원하고, Markdown을 지원하는 웹사이트들이 이 옵션을 켜놓고 있기 때문에 모르는 사람들이 많다. CommonMark에서 URL이나 메일 주소를 링크하려면 <와 >로 주소를 감싸야 한다.

이를 잘 이용하면 URL의 앞 뒤에 띄어쓰기를 하지 않고도 링크를 걸 수 있다는 장점도 된다.

최근에 오랫동안 쓰던 키보드가 망가져서 큰 맘 먹고 프리플로우 Archon M1 PRO MAX를 질렀는데, 요즘 키보드는 다 WebHID 가지고 웹 드라이버로 설정하는 것 같다. 자바스크립트니까 뜯기 쉽겠거니 싶어서 살펴 봤는데 커스텀 HID 레포트를 보낼 수 있는 기능을 사용해서 명령들을 나열해 놓았고, 개중에는 롬을 통으로 날리는 것도 가감없이 노출되어 있길래 음 역시 WebHID 같은 건 웹에 넣을 기능이 못된다는 결론을 내렸다. 가볍게 함수 목록만 요약해서 https://gist.github.com/lifthrasiir/c79c90ecf697b1e6dc73e83f32984499에 올렸다.

애플리케이션 개발 측면에서 본 Drizzle ORM 대 Kysely 비교

------------------------------

# Drizzle ORM vs Kysely 비교 요약

## Drizzle ORM의 장점

- *스키마 정의의 직관성* : 선언적 방식의 스키마 정의가 가능하며, 이로부터 자동으로 CREATE TABLE SQL 생성이 가능.

- *자동화된 마이그레이션* : 스키마 변경사항을 자동으로 감지하여 SQL 마이그레이션 파일 생성이 가능.

- 직관…

------------------------------

https://news.hada.io/topic?id=19805&utm_source=googlechat&utm_medium=bot&utm_campaign=1834