hackers.pub 로그인 페이지에서,

가입하려 이메일을 넣었더니, 베타 서비스라 안된다는 메시지가 뜹니다. 음, 제 생각엔 이 메시지는 로그인 폼에 뭔가를 입력하기 전에 나오는 게 더 부드럽지 않을까 싶어요.

#HackersPub

bgl gwyng

@bgl@hackers.pub · 99 following · 124 followers

GitHub

- @bglgwyng

https://github.com/dahlia/hackerspub/pull/12

해커스펍의 멘션 기능에 가독성 개선이 필요할 것 같아서 제안하는 느낌으로 PR은 올렸는데, 다른 분들도 어떤 의견을 가지고 계실지 모르겠다

나와주시는 한 분 한 분 너무 감사하게 생각하고, 비상행동은 언제든지 광장을 열기 위해서 계속해서 노력을 해나갈 테니까 함께, 끝까지 함께 해주셨으면 좋겠다 이런 말씀을 드리고 싶습니다."

![]() @curry박준규 확장이 하도 많아서 뭐가 있는지 다 알기가 어려운 것 같아요… 😂

@curry박준규 확장이 하도 많아서 뭐가 있는지 다 알기가 어려운 것 같아요… 😂

![]() @hongminhee洪 民憙 (Hong Minhee) 이런 표현이 있습니다.

@hongminhee洪 民憙 (Hong Minhee) 이런 표현이 있습니다.

GHC has more flags than the UN.

![]() @hongminhee洪 民憙 (Hong Minhee)

@hongminhee洪 民憙 (Hong Minhee)  I can't agree more. 'Java sucks' doesn't apply here at least. Subtyping plays really well in unioning error types.

I can't agree more. 'Java sucks' doesn't apply here at least. Subtyping plays really well in unioning error types.

![]() @bglbgl gwyng Absolutely! You make a great point about subtyping—it's one of Java's underappreciated strengths for error handling. The exception hierarchy lets you catch specific exceptions or their broader subtypes as needed, giving you flexible error composition without extra syntax.

@bglbgl gwyng Absolutely! You make a great point about subtyping—it's one of Java's underappreciated strengths for error handling. The exception hierarchy lets you catch specific exceptions or their broader subtypes as needed, giving you flexible error composition without extra syntax.

![]() bgl gwyng shared the below article:

bgl gwyng shared the below article:

Revisiting Java's Checked Exceptions: An Underappreciated Type Safety Feature

洪 民憙 (Hong Minhee) @hongminhee@hackers.pub

Despite their bad reputation in the Java community, checked exceptions provide superior type safety comparable to Rust's Result<T, E> or Haskell's Either a b—we've been dismissing one of Java's best features all along.

Introduction

Few features in Java have been as consistently criticized as checked exceptions. Modern Java libraries and frameworks often go to great lengths to avoid them. Newer JVM languages like Kotlin have abandoned them entirely. Many experienced Java developers consider them a design mistake.

But what if this conventional wisdom is wrong? What if checked exceptions represent one of Java's most forward-thinking features?

In this post, I'll argue that Java's checked exceptions were ahead of their time, offering many of the same type safety benefits that are now celebrated in languages like Rust and Haskell. Rather than abandoning this feature, we should consider how to improve it to work better with modern Java's features.

Understanding Java's Exception Handling Model

To set the stage, let's review how Java's exception system works:

-

Unchecked exceptions (subclasses of

RuntimeExceptionorError): These don't need to be declared or caught. They typically represent programming errors (NullPointerException,IndexOutOfBoundsException) or unrecoverable conditions (OutOfMemoryError). -

Checked exceptions (subclasses of

Exceptionbut notRuntimeException): These must either be caught withtry/catchblocks or declared in the method signature withthrows. They represent recoverable conditions that are outside the normal flow of execution (IOException,SQLException).

Here's how this works in practice:

// Checked exception - compiler forces you to handle or declare it

public void readFile(String path) throws IOException {

Files.readAllLines(Path.of(path));

}

// Unchecked exception - no compiler enforcement

public void processArray(int[] array) {

int value = array[array.length + 1]; // May throw ArrayIndexOutOfBoundsException

}The Type Safety Argument for Checked Exceptions

At their core, checked exceptions are a way of encoding potential failure modes into the type system via method signatures. This makes certain failure cases part of the API contract, forcing client code to explicitly handle these cases.

Consider this method signature:

public byte[] readFileContents(String filePath) throws IOExceptionThe throws IOException clause tells us something critical: this method might fail in ways related to IO operations. The compiler ensures you can't simply ignore this fact. You must either:

- Handle the exception with a try-catch block

- Propagate it by declaring it in your own method signature

This type-level representation of potential failures aligns perfectly with principles of modern type-safe programming.

Automatic Propagation: A Hidden Advantage

One often overlooked advantage of Java's checked exceptions is their automatic propagation. Once you declare a method as throws IOException, any exception that occurs is automatically propagated to the caller without additional syntax.

Compare this with Rust, where you must use the ? operator every time you call a function that returns a Result:

// Rust requires explicit propagation with ? for each call

fn read_and_process(path: &str) -> Result<(), std::io::Error> {

let content = std::fs::read_to_string(path)?;

process_content(&content)?;

Ok(())

}

// Java automatically propagates exceptions once declared

void readAndProcess(String path) throws IOException {

String content = Files.readString(Path.of(path));

processContent(content); // If this throws IOException, it's automatically propagated

}In complex methods with many potential failure points, Java's approach leads to cleaner code by eliminating the need for repetitive error propagation markers.

Modern Parallels: Result Types in Rust and Haskell

The approach of encoding failure possibilities in the type system has been adopted by many modern languages, most notably Rust with its Result<T, E> type and Haskell with its Either a b type.

In Rust:

fn read_file_contents(file_path: &str) -> Result<Vec<u8>, std::io::Error> {

std::fs::read(file_path)

}When calling this function, you can't just ignore the potential for errors—you need to handle both the success case and the error case, often using the ? operator or pattern matching.

In Haskell:

readFileContents :: FilePath -> IO (Either IOException ByteString)

readFileContents path = try $ BS.readFile pathAgain, the caller must explicitly deal with both possible outcomes.

This is fundamentally the same insight that motivated Java's checked exceptions: make failure handling explicit in the type system.

Valid Criticisms of Checked Exceptions

If checked exceptions are conceptually similar to these widely-praised error handling mechanisms, why have they fallen out of favor? There are several legitimate criticisms:

1. Excessive Boilerplate in the Call Chain

The most common complaint is the boilerplate required when propagating exceptions up the call stack:

void methodA() throws IOException {

methodB();

}

void methodB() throws IOException {

methodC();

}

void methodC() throws IOException {

// Actual code that might throw IOException

}Every method in the chain must declare the same exception, creating repetitive code. While automatic propagation works well within a method, the explicit declaration in method signatures creates overhead.

2. Poor Integration with Functional Programming

Java 8 introduced lambdas and streams, but checked exceptions don't play well with them:

// Won't compile because map doesn't expect functions that throw checked exceptions

List<String> fileContents = filePaths.stream()

.map(path -> Files.readString(Path.of(path))) // Throws IOException

.collect(Collectors.toList());This forces developers to use awkward workarounds:

List<String> fileContents = filePaths.stream()

.map(path -> {

try {

return Files.readString(Path.of(path));

} catch (IOException e) {

throw new UncheckedIOException(e); // Wrap in an unchecked exception

}

})

.collect(Collectors.toList());3. Interface Evolution Problems

Adding a checked exception to an existing method breaks all implementing classes and calling code. This makes evolving interfaces over time difficult, especially for widely-used libraries and frameworks.

4. Catch-and-Ignore Anti-Pattern

The strictness of checked exceptions can lead to the worst possible outcome—developers simply catching and ignoring exceptions to make the compiler happy:

try {

// Code that might throw

} catch (Exception e) {

// Do nothing or just log

}This is worse than having no exception checking at all because it provides a false sense of security.

Improving Checked Exceptions Without Abandoning Them

Rather than abandoning checked exceptions entirely, Java could enhance the existing system to address these legitimate concerns. Here are some potential improvements that preserve the type safety benefits while addressing the practical problems:

1. Allow lambdas to declare checked exceptions

One of the biggest pain points with checked exceptions today is their incompatibility with functional interfaces. Consider how much cleaner this would be:

// Current approach - forced to handle or wrap exceptions inline

List<String> contents = filePaths.stream()

.map(path -> {

try {

return Files.readString(Path.of(path));

} catch (IOException e) {

throw new RuntimeException(e);

}

})

.collect(Collectors.toList());

// Potential future approach - lambdas can declare exceptions

List<String> contents = filePaths.stream()

.map((String path) throws IOException -> Files.readString(Path.of(path)))

.collect(Collectors.toList());This would require updating functional interfaces to support exception declarations:

@FunctionalInterface

public interface Function<T, R, E extends Exception> {

R apply(T t) throws E;

}2. Generic exception types in throws clauses

Another powerful enhancement would be allowing generic type parameters in throws clauses:

public <E extends Exception> void processWithException(Supplier<Void, E> supplier) throws E {

supplier.get();

}This would enable much more flexible composition of methods that work with different exception types, bringing some of the flexibility of Rust's Result<T, E> to Java's existing exception system.

3. Better support for exception handling in functional contexts

Unlike Rust which requires the ? operator for error propagation, Java already automatically propagates checked exceptions when declared in the method signature. What Java needs instead is better support for checked exceptions in functional contexts:

// Current approach for handling exceptions in streams

List<String> contents = filePaths.stream()

.map(path -> {

try {

return Files.readString(Path.of(path));

} catch (IOException e) {

throw new RuntimeException(e); // Lose type information

}

})

.collect(Collectors.toList());

// Hypothetical improved API

List<String> contents = filePaths.stream()

.mapThrowing(path -> Files.readString(Path.of(path))) // Preserves checked exception

.onException(IOException.class, e -> logError(e))

.collect(Collectors.toList());4. Integration with Optional<T> and Stream<T> APIs

The standard library could be enhanced to better support operations that might throw checked exceptions:

// Hypothetical API

Optional<String> content = Optional.ofThrowable(() -> Files.readString(Path.of("file.txt")));

content.ifPresentOrElse(

this::processContent,

exception -> log.error("Failed to read file", exception)

);Comparison with Other Languages' Approaches

It's worth examining how other languages have addressed the error handling problem:

Rust's Result<T, E> and ? operator

Rust's approach using Result<T, E> and the ? operator shows how propagation can be made concise while keeping the type safety benefits. The ? operator automatically unwraps a successful result or returns the error to the caller, making propagation more elegant.

However, Rust's approach requires explicit propagation at each step, which can be more verbose than Java's automatic propagation in certain scenarios.

Kotlin's Approach

Kotlin made all exceptions unchecked but provides functional constructs like runCatching that bring back some type safety in a more modern way:

val result = runCatching {

Files.readString(Path.of("file.txt"))

}

result.fold(

onSuccess = { content -> processContent(content) },

onFailure = { exception -> log.error("Failed to read file", exception) }

)This approach works well with Kotlin's functional programming paradigm but lacks compile-time enforcement.

Scala's Try[T], Either[A, B], and Effect Systems

Scala offers Try[T], Either[A, B], and various effect systems that encode errors in the type system while integrating well with functional programming:

import scala.util.Try

val fileContent: Try[String] = Try {

Source.fromFile("file.txt").mkString

}

fileContent match {

case Success(content) => processContent(content)

case Failure(exception) => log.error("Failed to read file", exception)

}This approach preserves type safety while fitting well with Scala's functional paradigm.

Conclusion

Java's checked exceptions were a pioneering attempt to bring type safety to error handling. While the implementation has shortcomings, the core concept aligns with modern type-safe approaches to error handling in languages like Rust and Haskell.

Copying Rust's Result<T, E> might seem like the obvious solution, but it would represent a radical departure from Java's established paradigms. Instead, targeted enhancements to the existing checked exceptions system—like allowing lambdas to declare exceptions and supporting generic exception types—could preserve Java's unique approach while addressing its practical limitations.

The beauty of such improvements is that they'd maintain backward compatibility while making checked exceptions work seamlessly with modern Java features like lambdas and streams. They would acknowledge that the core concept of checked exceptions was sound—the problem was in the implementation details and their interaction with newer language features.

So rather than abandoning checked exceptions entirely, perhaps we should recognize them as a forward-thinking feature that was implemented before its time. As Java continues to evolve, we have an opportunity to refine this system rather than replace it.

In the meantime, next time you're tempted to disparage checked exceptions, remember: they're not just an annoying Java quirk—they're an early attempt at the same type safety paradigm that newer languages now implement with much celebration.

What do you think? Could these improvements make checked exceptions viable for modern Java development? Or is it too late to salvage this controversial feature? I'm interested in hearing your thoughts in the comments.

모든 자바스크립트 개발자들이 단 하나의 패키지 매니저와 단 하나의 빌드 시스템, 단 하나의 모듈 시스템을 사용하면 좋겠다고 진심으로 생각한다

C++ 표준화 위원회(WG21)에게 C++의 원 저자인 비야네 스트롭스트룹Bjarne Stroustrup이 보낸 메일이 이번 달 초에 본인에 의해 공개된 모양이다. C++가 요즘 안전하지 않은 언어라고 열심히 얻어 맞고 있는 게 싫은지 프로파일(P3081)이라고 하는 언어 부분집합을 정의하려고 했는데, 프로파일이 다루는 문제들이 아주 쉬운 것부터 연구가 필요한 것까지 한데 뒤섞여 있어 구현이 매우 까다롭기에 해당 제안이 적절하지 않음을 올해 초에 가멸차게 까는 글(P3586)이 올라 오자 거기에 대한 응답으로 작성된 것으로 보인다. 더 레지스터의 표현을 빌면 "(본지가 아는 한) 스트롭스트룹이 이 정도로 강조해서 말하는 건 2018년 이래 처음"이라나.

여론은 당연히 호의적이지 않은데, 기술적인 반론이 대부분인 P3586과는 달리 해당 메일은 원래 공개 목적이 아니었음을 감안해도 기술적인 얘기는 쏙 빼 놓고 프로파일이 "코드를 안 고치고도 안전성을 가져 갈 수 있다"는 허황된 주장에 기반해 그러니까 프로파일을 당장 집어 넣어야 한다고 주장하고 있으니 그럴 만도 하다. 스트롭스트룹이 그렇게 이름을 언급하지 않으려고 했던 러스트를 굳이 들지 않아도, 애당초 (이 또한 계속 부정하고 싶겠지만) C++의 주요 장점 중 하나였던 강력한 C 호환성이 곧 메모리 안전성의 가장 큰 적이기 때문에 프로파일이 아니라 프로파일 할아버지가 와도 안전성을 진짜로 확보하려면 코드 수정이 필수적이고, 프로파일이 그 문제를 해결한다고 주장하는 건 눈 가리고 아웅이라는 것을 이제는 충분히 많은 사람들이 깨닫지 않았는가. 스트롭스트룹이 허황된 주장을 계속 반복하는 한 C++는 안전해질 기회가 없을 듯 하다.

타임라인과 RSS 피드에 단문 없이 게시글만 보는 필터를 추가했습니다.

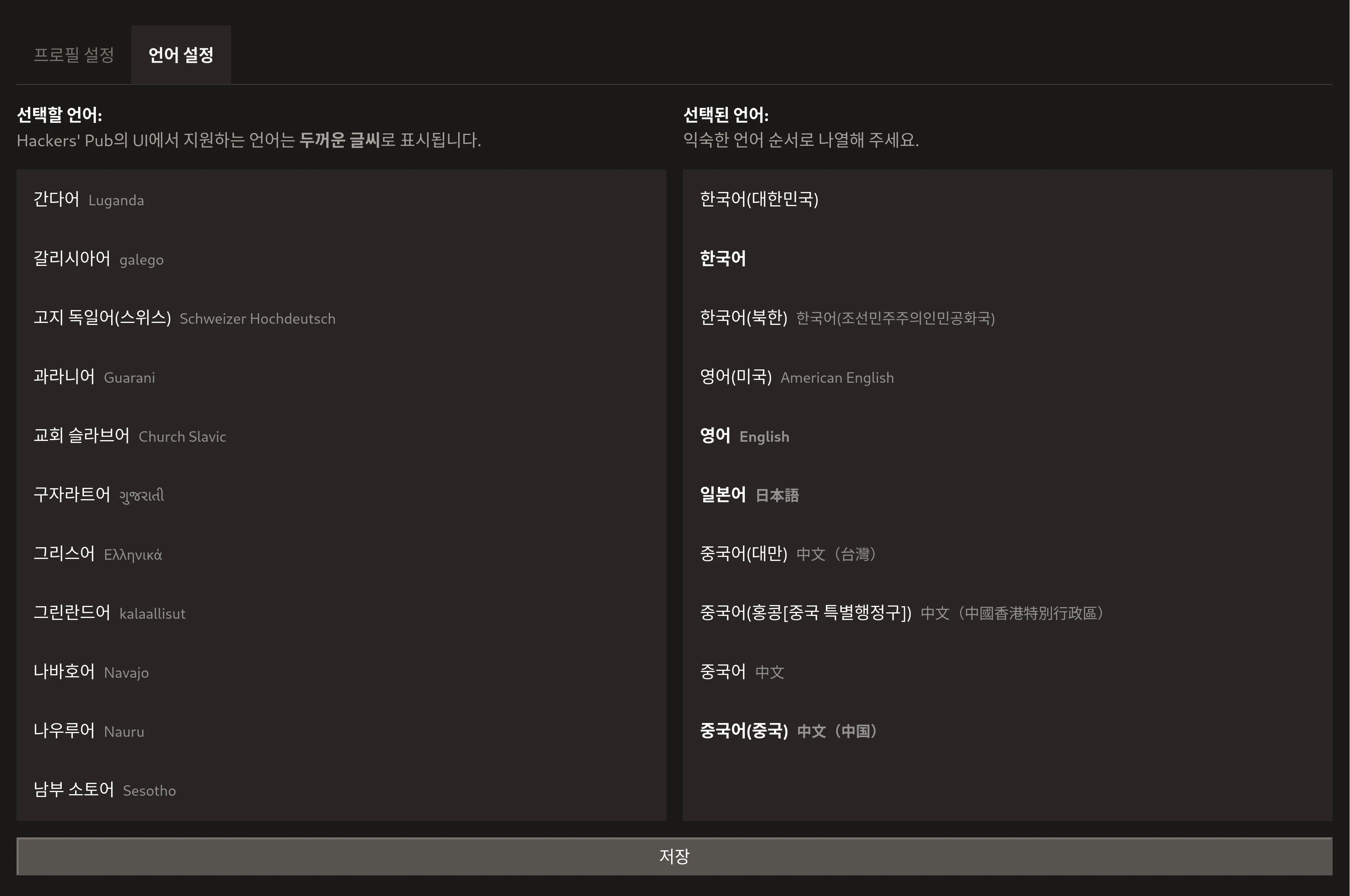

![]() @dwndiaowinner 님 덕분애 Hackers' Pub에 중국어 번역이 추가되었습니다!

@dwndiaowinner 님 덕분애 Hackers' Pub에 중국어 번역이 추가되었습니다!

또한, 언어 설정이 추가되어, 자신이 선호하는 복수의 언어를 선택할 수 있게 되었습니다. 이 설정은 당장은 팔로 추천에만 쓰이고 있지만, 앞으로 자동 번역이나 알고리즘 타임라인 등에 요긴하게 쓰일 예정입니다.

asbubam 님의 내가 만난 멋진 SRE

SRE 에 대한 얘기지만 멋대로(?) 개발자에 대입해서 보았습니다. 와닿는 내용을 일부 인용해 보면

여기 우리 다 처음에 그랬고 오늘도 여전히 매일 고민하고, 부딪히고, 배우면서 앞으로 나아가고 있으니까

멋진 SRE는, 도무지 답이 보이지 않는 문제를 만나도, “원래 그런거니까 흐흐” 하고 문제에 달려들어요. 내 힘으로 부족한 일은, 옆에있는 동료와 함께 반드시 해결할 수 있다고 믿어요

회사 동료들에게도 말해주고 싶은 내용들이네요. 동료들이 있으니께 걱정하지 말고 나아가라구요.

이番에 ![]() @lqezPark Hyunwoo 님의 《우리의 코드를 찾아서》에 出演하여 #페디버스, #ActivityPub, #Fedify, #Hollo 等에 關해 이야기를 나눴습니다. Fedify와 Hollo의 開發 祕話 같은 게 궁금하시다면 한 番 보셔도 재밌을지도 모르겠습니다. ㅎㅎㅎ

@lqezPark Hyunwoo 님의 《우리의 코드를 찾아서》에 出演하여 #페디버스, #ActivityPub, #Fedify, #Hollo 等에 關해 이야기를 나눴습니다. Fedify와 Hollo의 開發 祕話 같은 게 궁금하시다면 한 番 보셔도 재밌을지도 모르겠습니다. ㅎㅎㅎ

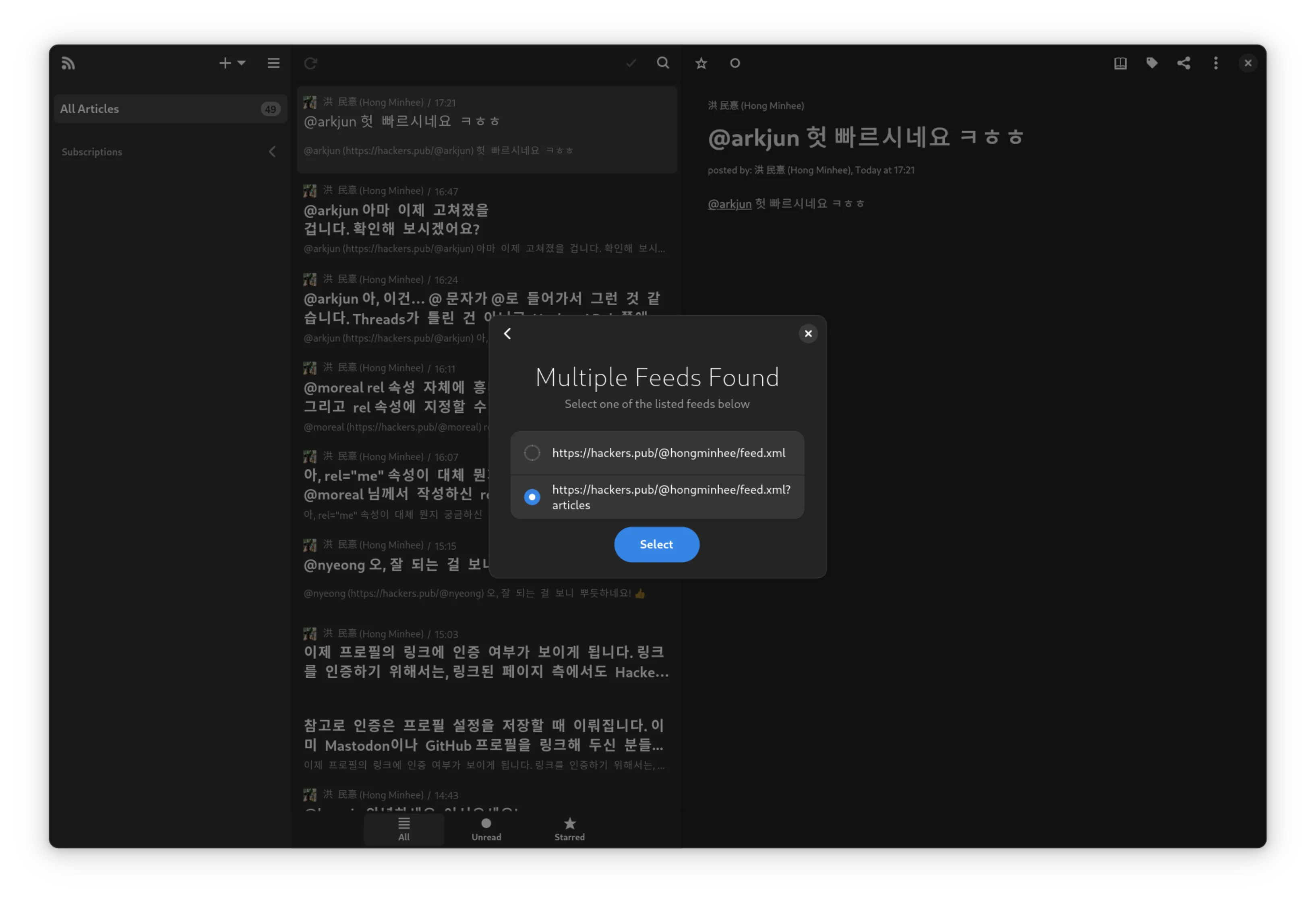

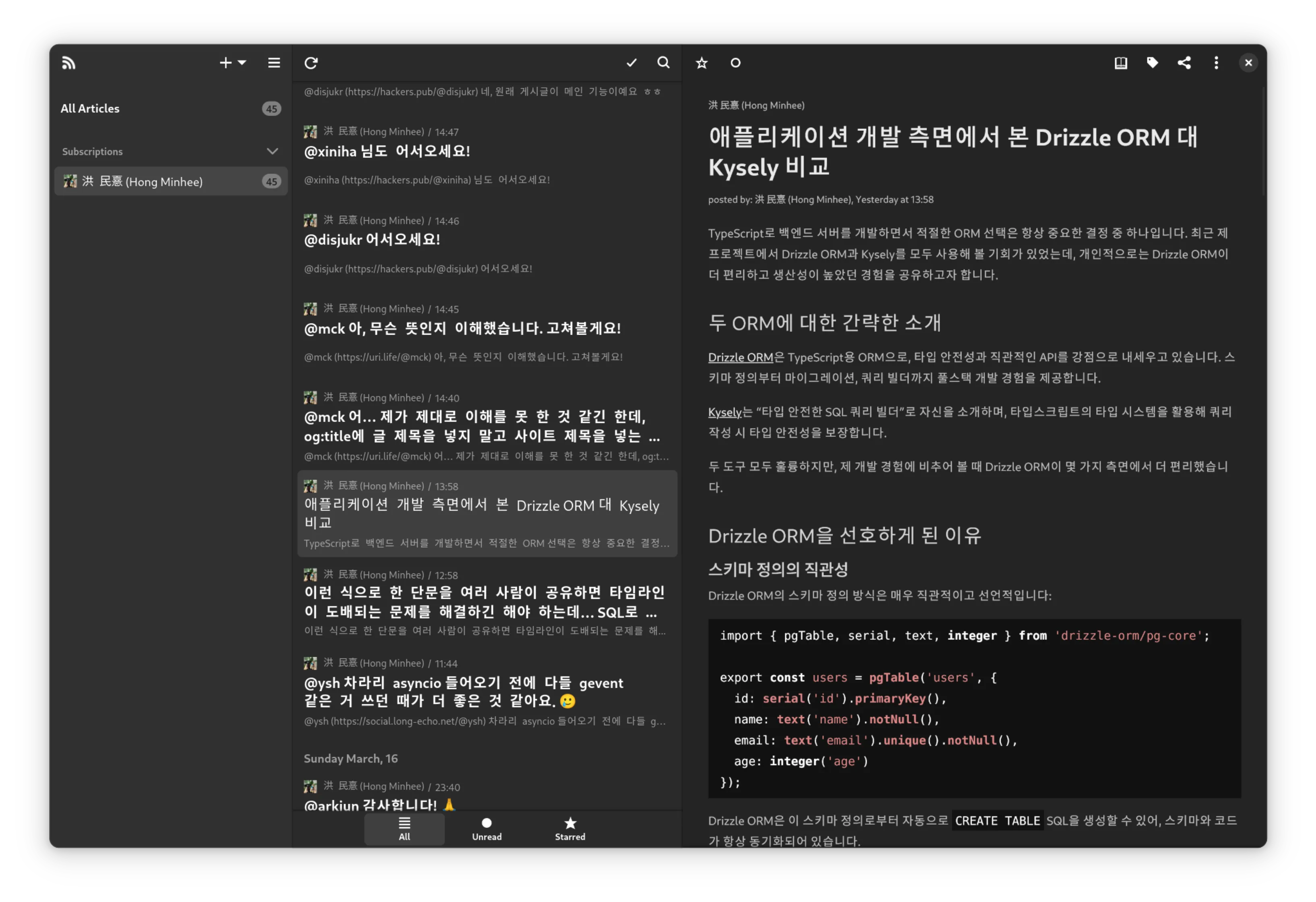

Hackers' Pub에 RSS 기능을 추가했습니다. 정확히는 RFC 4287, 일명 Atom 명세를 구현했습니다. RSS 디스커버리도 구현했기 때문에, Hackers' Pub 사용자의 프로필 페이지 링크를 RSS 앱에 추가하면 구독이 가능합니다. 확실한(?) 피드 링크를 알고 싶으시면 프로필 링크 뒤에 /feed.xml을 붙이시면 됩니다. 예를 들어, 제 피드 링크는 https://hackers.pub/@hongminhee/feed.xml입니다.

어렸을 때는 Smalltalk나 Lisp 같은 언어에 마음을 많이 빼앗겼는데 (아마도 당시 쿨한 언어였던 Python이나 Ruby의 영향…) Haskell을 접한 뒤로는 언어 취향이 아주 많이 바뀐 것 같다. 일단 동적 타입 언어를… 싫어하는 정도까진 아니지만, 쓰면서 불안함을 느끼게 됐다.

이제 게시글(긴 글)도 단문처럼 공유가 가능해졌습니다. 그리고, 타임라인에 게시글에 대한 댓글이 보이는 방식을 수정하였습니다.

https://wikidocs.net/book/14314

Langchain 관련해서 한국어로 정리가 잘 정리되어 있는 듯

하스켈 패키지 검색 엔진이자 웹 서비스인 후글(Hoogle)은 서비스에 종종 문제가 생기곤 합니다. 그럴 때는 다음과 같은 대체 서비스를 이용해보세요!

한편 후글을 로컬에 설치해서 사용하는 것도 가능합니다. 잦은 서비스 문제에 질렸다면 로컬에 후글을 설치해보세요!

그리고 만약 당신이 부자라면⋯ 하스켈 재단에 기부해주세요⋯

우분투에서 뻗어나온 운영체제 이름으로 고군분투 좋은 것 같지 않아? (엉망진창 비난과 핍박을 받는다)

모바일 뷰에서 타임라인 레이아웃이 깨지던 문제를 해결했습니다. 제보해주신 ![]() @bglbgl gwyng 님께 감사드립니다!

@bglbgl gwyng 님께 감사드립니다!

モバイルビューでタイムラインのレイアウトが崩れる問題を修正しました。報告してくださった ![]() @bglbgl gwyng さんに感謝します!

@bglbgl gwyng さんに感謝します!

쉘스크립트처럼 oci 컨테이너들을 조합하는 언어가 있으면 좋겠다.

컨테이너는 샌드박싱된 파일시스템을 입력으로 받아 출력으로 쓰고, 그런 컨테이너들을 (| pipe operator로 stdin/stdout을 잇듯이) 조합하는 것이다. 그리고 이때 각 컨테이너가 필요로하는 입력 파일/디렉토리들에 대해 일종의 타입 체크를 해서 no such file or directory가 뜨는것을 막아줄수 있을것이다.

사실 yaml등으로 작성하는 CI/CD 설정 파일들이 비슷한 기능을 하고있는데, 이걸 좀더 멀쩡한 언어로, 로컬에서도 쓸수있으면 좋겠다.

![]() @bglbgl gwyng 예전에 Bass라는 언어를 우연히 본 적이 있는데, 그게 떠오르네요. 말씀하신 것과는 좀 다르지만요.

@bglbgl gwyng 예전에 Bass라는 언어를 우연히 본 적이 있는데, 그게 떠오르네요. 말씀하신 것과는 좀 다르지만요.

프로그래밍 언어 하스켈 패키지 중에 연합우주와 관련 있는 것을 찾아봤더니 webfinger-client가 있습니다. 2016년에 마지막 업로드가 되었고 너무 오래 돼서 빌드도 안 되는 상태입니다. LLM 도움을 받아 빌드 가능하게 패치하고 메인테이너에게 연락을 해봤습니다. 답장은 아직 없고 사실 메일을 보낸 지 24시간이 지나지도 않았지만 왠지 연락이 오지 않을 것만 같습니다. 급한 마음에(왜 급한지 모르겠지만) 하스켈 포럼에 패키지를 인수하고 싶다고 글을 남겼습니다. 좋은 소식이 오길 기대해봅니다.

https://discourse.haskell.org/t/taking-over-the-webfinger-client-package-maintenance/11628

어느 디자인 포트폴리오 회사에서 GIF 지원을 중단하고 WebP 만을 사용하게 강제하면서, 주변 지인이 CLI로 변환하는 불편을 겪고 있었기 때문에 간단한 웹 앱을 만들었습니다. 이전에 동작은 만들었었는데 테마나 스타일링이나 조금 덧 붙여서 공개했습니다.

서버에 GIF 파일을 보내고 다시 받는 대신, 브라우저에서 변환하여 다운받을 수 있습니다.